A Simple Merch Store Backend: Distributed and Cloud Computing Assignment 2

- Distributed Systems

- 2025-12-30

- 424 Views

- 0 Comments

- 8750 Words

Scores

95+10=105 (extra: 5)

Summary: The impl is nice in general, and the report is awesome! Yes, this is an assignment where you should follow certain instructions and submit certain stuff, but just like what you mentioned, this can also be a journey to explore way more insteresting things about system performance & optimization techniques. Thank you for being willing to spend so much time on this assignment, and hope you can always learn more and have fun!

API Service

Order:

- GetOrder: you use JWT to auth as a user with user_id, but then fetch the order only with order_id, not relying on that user_id - this means user A can check order 2 from user B as long as user A logins and has a token to pass auth (-1) same for some other APIs

Monitoring:

-

you impl a streaming RPC, but use it as a unary RPC to send one single log every call - should call the stremaing RPC once and send multiple logs to the stream (-1)

-

nice log to include the service name so the load balancing behavior can be easily verified!

DB Service

Order:

- nice work to update product stock when handling order!

General:

-

you use

with connto support automatic rollback, which seems fine (-0) -

gRPC Error Handling: some ops like CreateOrder did not set gRPC status code + detail on error (-0 since I see you did it with context.abort for other ops) should be consistent

Logging Service

General:

- gRPC Error Handling: should set gRPC status and details on error (-1)

Compose

Compose file:

-

should use .env to avoid writing credentials like DB user+password of POSTGRES_DSN in compose file (-1)

-

should depends_on service with condition service_ready, otherwise DB Service can fail before postgres is ready (even though it has started on its way to be ready) (-1)

Report Q1: nice infrastructure figure and impl flowchart!

Report Q2: nice tables and code explanation!

Report Q3: interesting Entity-Relationship graph to demonstrate our DB structure; and very nice explanation on how you make the data types consistent across OpenAPI Spec, gRPC, and DB. Nice work!

Report Q4: nice analysis and also great job to compare the message size with JSON!

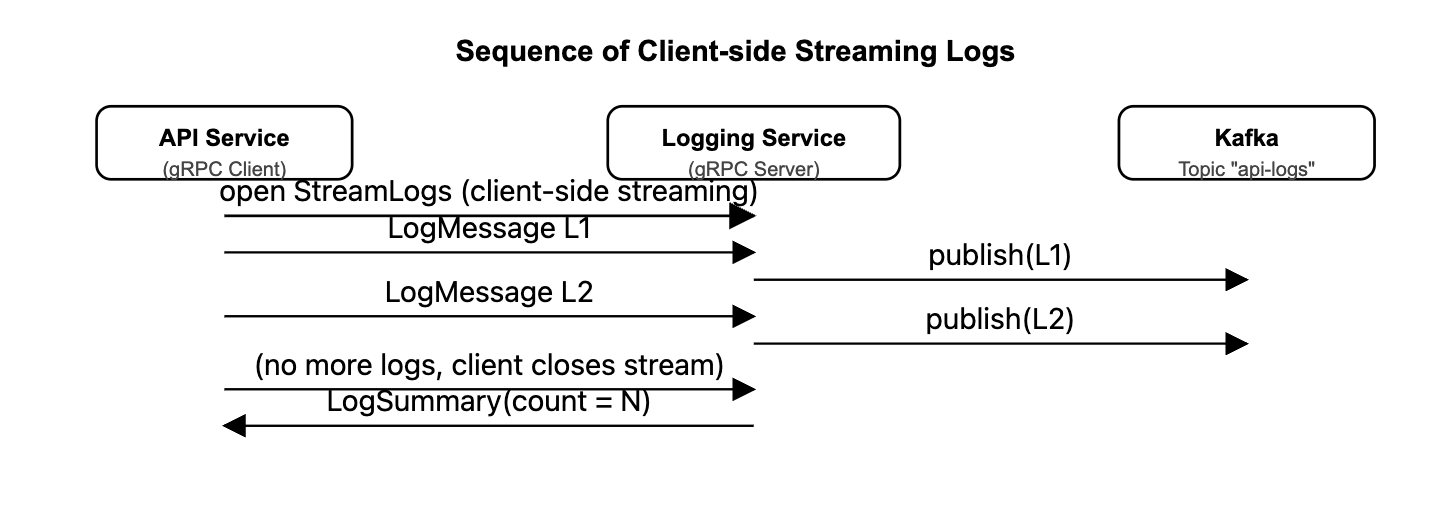

Report Q5: nice sequence diagram to clarify the expected client-side streaming logic. However, your impl in API Service actually yields 1 log message per RPC call: you pass in 1 dict object to the list

logs, which is transformed into a gRPC msg and yielded in an inner function - this inner generator function is passed to 1 RPC call. The correct way to reach the expected behavior you draw is likely: call stub.StreamLogs once with a generator function that repeatedly yield messages from a global message queue, then send the log message into the message queue, so it can be fetched and yielded by the generator function. You can dig a bit more into this if interested 🙂Report Q7: very conprehensive experiment results! The QPS experiment is very interesting, indicating certain cache layer / in-memory data store design might further improve the serving performance; the success rate test with Nginx examines a very realistic issue when requests are flooding through our app system - nice work!

1. Introduction

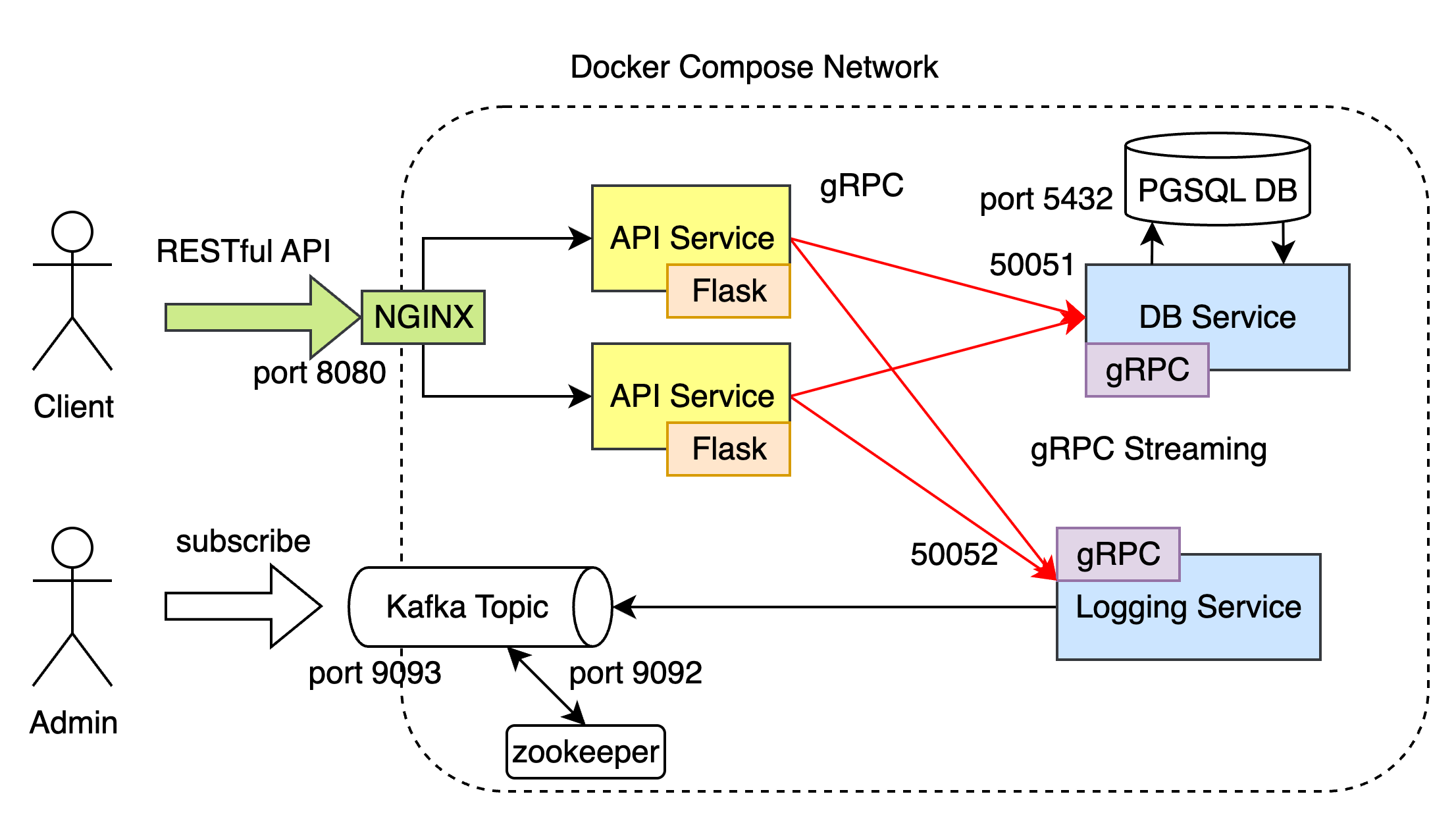

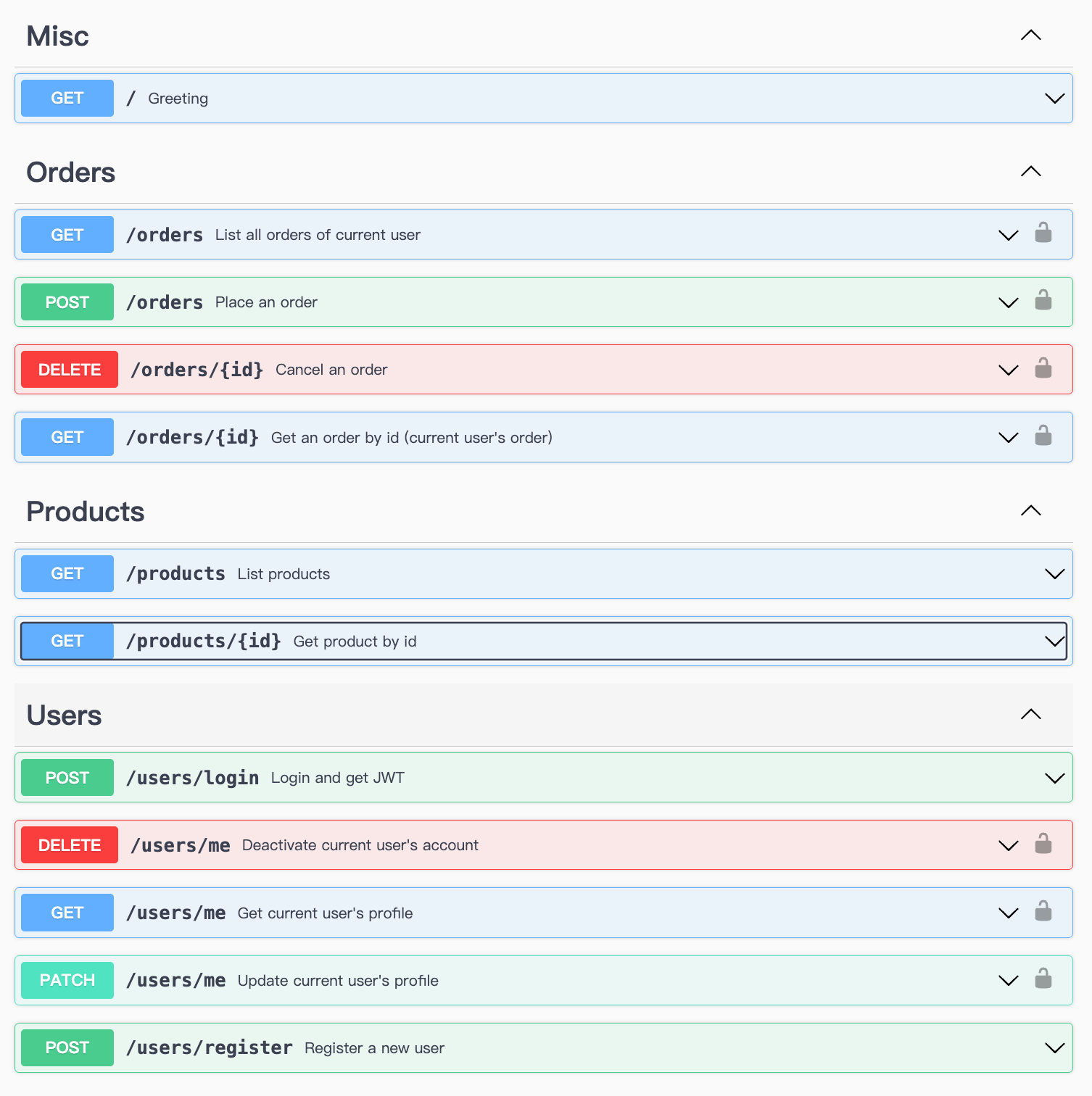

In this assignment, we need to implement a simple Merch Store backend with 3 micro service: API service, DB service and Logging Service. For API Service, we use An OpenAPI specification YAML to generate a Python Flask RESTful API Service. And we use gRPC to communicate with DB and Logging Service, which are generated by Proto files. All of them run in Docker network, and we support 2 RESTful API Service using NGINX.

The rest of the report are organized as following:

- For section "Overall Architecture", we introduce our main system design and philosophy.

- For section "Setup", we discuss how we mainly build the system. And we also discuss our procedures of our implementation for each component, like API decision, Database CRUD design, gRPC code implementation and docker network design.

- For section "API Design", we discuss APIs authentication and authentication logic.

- For section "Field Data", we discuss how we select data types for different definitions.

- Section "gRPC verification" selects an arbitrary Proto message from your definition and analyze how it is encoded into binary format.

- Section "client-side streaming gRPC" explain how the client-side streaming RPC works.

- Section "Docker and Docker Compose" shows docker files that let each service communicate with each other.

- Section "Experiments" shows swagger UI to show our API, and how we observe log from kafka. We also use tool

heyto show our system's QPS.

The report is a little long, since there are many details in the code.

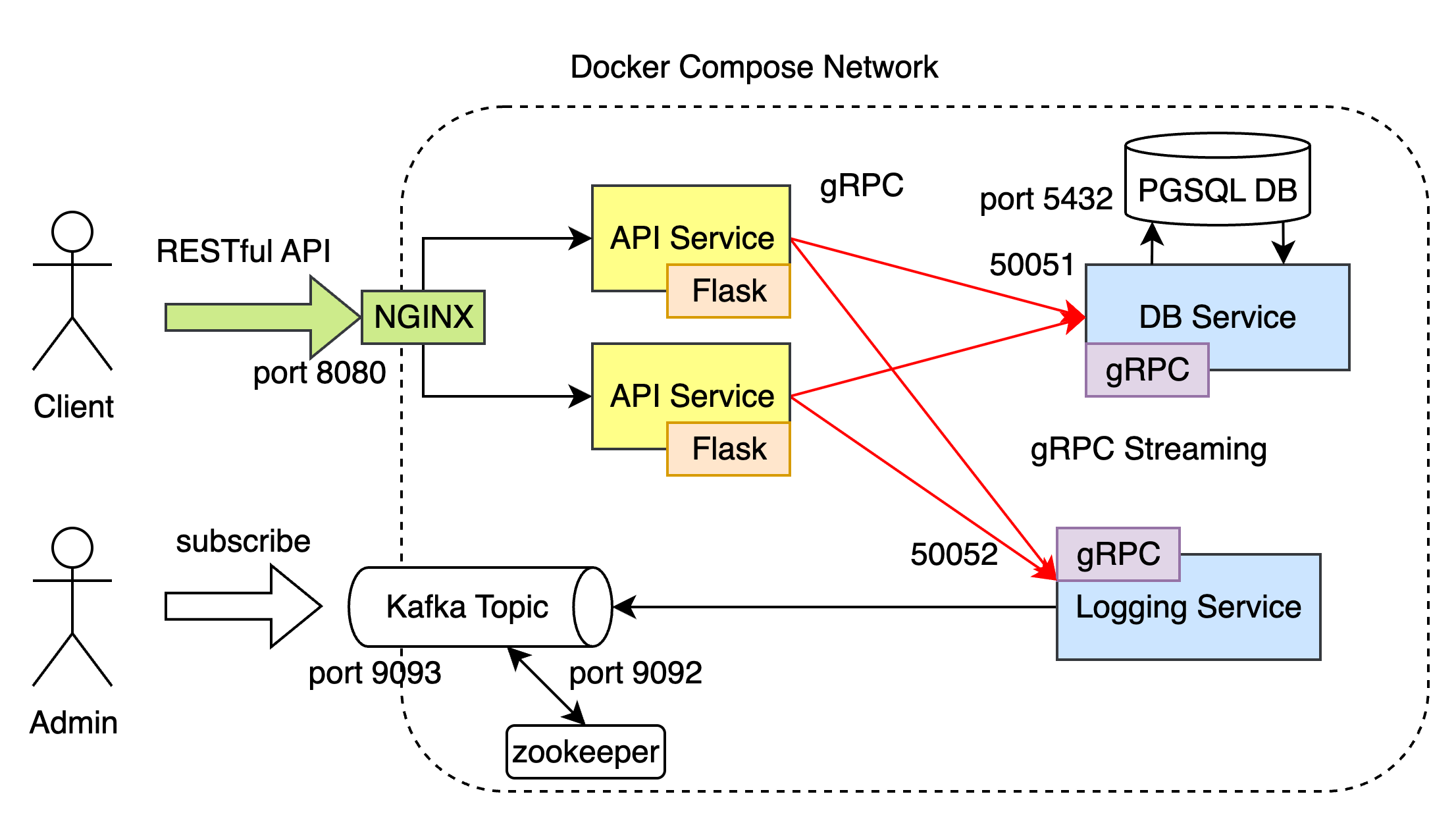

2. Overall Architecture

All of the service and database, Kafka and zookeeper run in Docker. For clients, they can use port 8080 to send RESTful API. The NGINX Server will catch the requests and send them to API Service with load balance scheduling (like Round Robin). The API Service runs in Flask framework will receive and deal with the requests. They will send gRPC communication to DB Service and Logging Service to deal with the requests. The DB Service will communicate with PG database on port 5432, while Logging Service will put logging message from port 9092 to Kafka, which the Administrator and know the logging information.

- The API Service include every API described in assignment.

- DB Service provide CRUD for products, users and orders.

- Logging Service provide communication with Kafka.

- RPC proto files, OpenAPI YAML file and Docker Compose File are provided.

- NGINX and it's config is also listed in file.

We also discuss some detail problems in these design:

- OpenAPI type of accessing API

- Generate JWT token when login, and use JWT to check accounts and orders

- Use string instead of float in

pricetag in OpenAPI and gRPC communication to prevent price mis-precision - Only store hash encrypted password in DB instead of plain password

- Prevent SQL injection in DB Service

- Concurrency in DB Service using

Transactionto prevent multi-thread conflict - Streaming gRPC for large log data across Logging Service and API Service.

We also do experiments on our API using hey to test the system QPS.

3. Setup

The setup is very easy since we use docker to compose everything.

To launch it, you can use the following command:

unzip 12211612_HaibinLai_A2.zip

cd codebase

# clean up and rebuild docker:

docker-compose down && docker-compose up --build -d

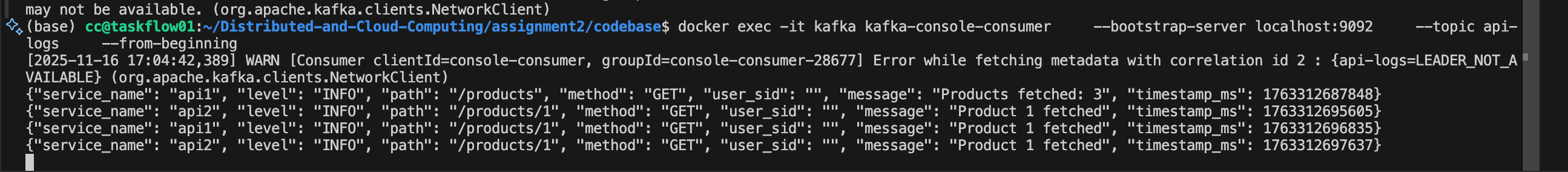

# to see logging service flow:

docker exec -it kafka kafka-console-consumer --bootstrap-server localhost:9092 --topic api-logs --from-beginning(If you encounter network problem, try to reconfig docker image source)

(Some python package may need to install)

How do I Implement the system?

In this section, I will explain how I set up the environment, generate code and implement the logic.

Environment setup

I prepared a working environment with:

- Python 3.10 with

condaandpipmanagement - Flask / Connexion (OpenAPI-based Flask framework)

- Python gRPC tools (

grpcio,grpcio-tools) - PostgreSQL (via Docker)

- Kafka + Zookeeper (via Docker)

- config like DB password etc

sudo apt update

pip install confluent-kafka, psycopg2-binary, grpcio, grpcio-tools, protobuf, connexion, Flask, swagger-ui-bundle

# install PostgreSQL

sudo apt install postgresql postgresql-contrib

sudo systemctl status postgresql

sudo apt install docker-compose

# stop local pgsql

sudo systemctl stop postgresql

docker-compose down && docker-compose up --build -dpostgre docker compose:

Change your postgres database username, passwd and db config in docker compose.yml . So that you can build the images correctly.

services:

# database for persistant data storage

postgres:

image: postgres:17

container_name: postgres

hostname: postgres

environment:

POSTGRES_USER: dncc. # my username

POSTGRES_PASSWORD: dncc # my passwd

POSTGRES_DB: goodsstore

ports:

- "5432:5432" # Expose PostgreSQL to localhost ("local:container")

volumes:

- pg_data:/var/lib/postgresql/data

- ./db-init:/docker-entrypoint-initdb.d build up the docker image and run the instance:

docker-compose -f compose.yaml down # clean the instance if possible

docker-compose -f compose.yaml up --build -d # build up the imagesAPI Decision

I break up the assignment requirement and generate a series of table to describe API just like:

| RESTful API | Method | Description | Must input | Can be null | Return |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /users/register | POST | Register | sid, password |

username, email |

SUCCESS/FAIL |

| /users/login | POST | Login | sid, password |

- | SUCCESS/FAIL |

| /users/me | GET | Get my profile | JWT | - | Profile info |

| /users/me | PATCH | Update my profile | JWT, your update things | - | SUCCESS/FAIL |

| /users/me | DELETE | Delete an account | JWT | - | SUCCESS/FAIL |

You can see the full of them in API Section.

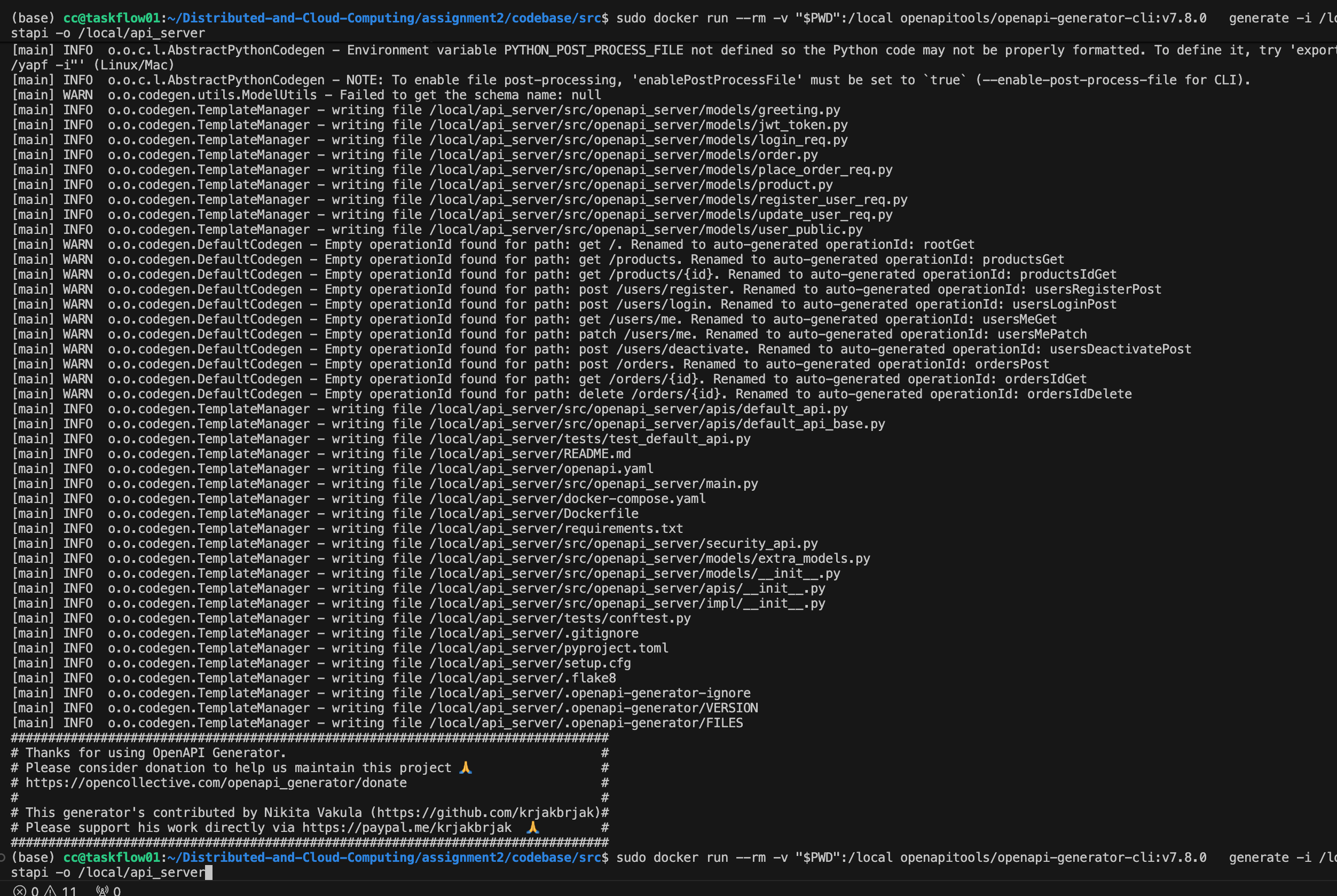

OpenAPI+Flask

I write down the OpenAPI to finish the frontend API. And I use deepseek to detect if some of my code is wrong. Then I use generator to generate the code:

docker run --rm \

-v ${PWD}:/local \

openapitools/openapi-generator-cli:v7.8.0 generate \

-i /local/openapi.yaml \

-g python-flask \

-o /local/server/python-flask

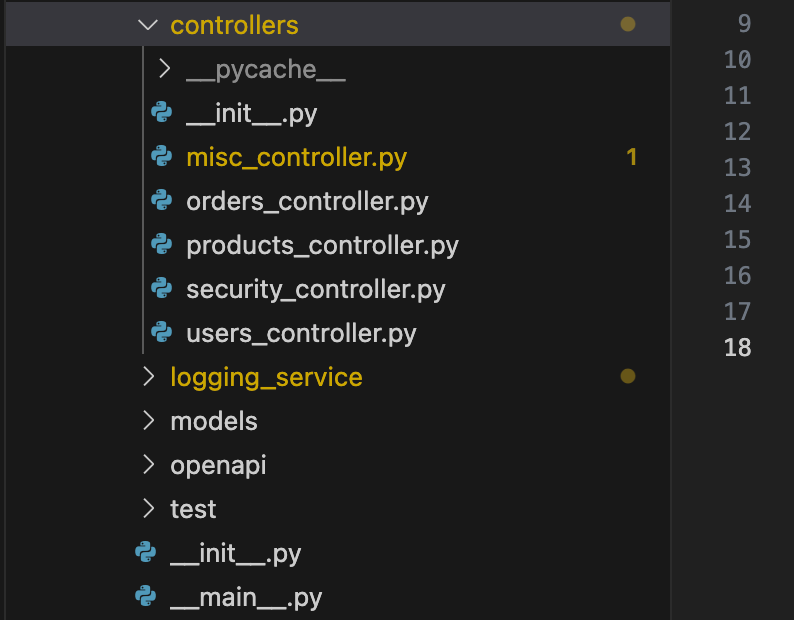

Flask Controller+JWT

the FLASK has several controller for api service. Here I finish and test them. (If they need to communicate with db, just write dummy code first and impl them later)

For example, the order_get help users know their orders:

def orders_get(page: int = None, page_size: int = None):

"""

GET /orders

- Get user_id from JWT token

- Take gRPC ListOrdersByUser

"""

# Get info from JWT

payload, err = _get_current_user_payload()

if err is not None:

return err

user_id = payload.get("user_id")

if user_id is None:

# logging service, impl later

logging_client.send_logs([{

"service_name": "api-service/orders",

"level": "ERROR",

"path": connexion.request.path,

"method": connexion.request.method,

"user_sid": "",

"message": "Invalid token: missing user_id"

}])

return _error("Invalid token: missing user_id", 401)

stub = _get_db_stub()

req = db_pb2.ListOrdersByUserRequest(

user_id=user_id,

page=page or 1,

page_size=page_size or 20,

)

try:

resp = stub.ListOrdersByUser(req)

except grpc.RpcError as e:

# logging service, impl later

logging_client.send_logs([{

"service_name": "api-service/orders",

"level": "ERROR",

"path": connexion.request.path,

"method": connexion.request.method,

"user_sid": "",

"message": f"DB service error: {e.code().name} - {e.details()}"

}])

return _error(f"DB service error: {e.code().name} - {e.details()}", 502)

orders = [_grpc_order_to_dict(o) for o in resp.orders]

# logging service, impl later

logging_client.send_logs([{

"service_name": "api-service/orders",

"level": "INFO",

"path": connexion.request.path,

"method": connexion.request.method,

"user_sid": "",

"message": f"Fetched {len(orders)} orders for user {user_id}"

}])

return _success(

"Orders fetched successfully",

data={

"items": orders,

"page": resp.page,

"page_size": resp.page_size,

"total_count": resp.total_count,

},

code=200,

)Here we use JWT to auth the userid.

JWT

The JWT will contain the sid and user_id

JWT_SECRET = os.environ.get("JWT_SECRET", "dev-secret")

JWT_ALGO = "HS256"

JWT_EXPIRE_HOURS = 12

def _get_current_user_payload():

"""

Authorization: Bearer xxx -> JWT -> payload。

"""

auth_header = connexion.request.headers.get("Authorization", "")

if not auth_header.startswith("Bearer "):

return None, _error("Missing or invalid Authorization header", 401)

token = auth_header.split(" ", 1)[1].strip()

try:

payload = pyjwt.decode(token, JWT_SECRET, algorithms=[JWT_ALGO])

except pyjwt.ExpiredSignatureError:

return None, _error("Token expired", 401)

except pyjwt.InvalidTokenError:

return None, _error("Invalid token", 401)

return payload, NoneDB Service

Serve using a connection pool:

def serve(port: int = 50051):

logging.basicConfig(level=logging.INFO)

init_pool()

server = grpc.server(futures.ThreadPoolExecutor(max_workers=10))

db_pb2_grpc.add_DbServiceServicer_to_server(DbService(), server)

server.add_insecure_port(f"[::]:{port}")

server.start()

logging.info("DB gRPC server started on port %d", port)

try:

server.wait_for_termination()

finally:

global POOL

if POOL is not None:

POOL.closeall()

POOL = None

logging.info("DB connection pool closed.")

if __name__ == "__main__":

serve()We can have 10 connector at one time:

def init_pool():

global POOL

if POOL is not None:

return

dsn = os.environ.get("POSTGRES_DSN")

if not dsn:

dsn = "dbname=goodsstore user=dncc password=dncc host=postgres port=5432"

logging.info(f"Initializing DB connection pool with DSN: {dsn}")

POOL = SimpleConnectionPool(minconn=1, maxconn=10, dsn=dsn)

def get_connection():

if POOL is None:

init_pool()

return POOL.getconn()

def release_connection(conn):

if POOL is not None:

POOL.putconn(conn)

else:

conn.close()Some of the CRUD example:

We use Database Transaction to make sure concurrency. with conn: wraps everything in one transaction. If any exception is raised inside, psycopg2 will automatically ROLLBACK when leaving the block. Any concurrent CreateOrder requests targeting the same product must wait until the current transaction finishes. Two customers cannot purchase the same remaining items at the same time, the stock value read from the database is always the latest and consistent, all subsequent updates to the product row happen safely. This is the standard technique for avoiding lost updates and overselling under PostgreSQL’s default READ COMMITTED isolation level.

To prevent SQL injection, all database queries in the DB Service are executed using parameterized statements (e.g.,

WHERE sid = %swith(request.sid,)in psycopg2) instead of string concatenation. User inputs are always passed as bound parameters, so they are treated as data rather than executable SQL.Use Decimal rather than float to compute the total price. And we also check the number and price that from DB.

# ---- Orders ----

def CreateOrder(self, request, context):

"""

CreateOrder 逻辑说明(在一个事务里完成):

1. 使用 SELECT ... FOR UPDATE 锁定商品行,读取 price 与 stock

2. 校验 quantity 范围(1~3)以及库存是否足够

3. 基于数据库中的 price 计算 total_price(使用 Decimal 处理金额)

4. 向 orders 表插入新订单记录,并返回生成的订单信息

5. 扣减 products 表中的库存

所有 SQL 操作都使用参数化查询(%s + 参数元组),防止 SQL 注入。

价格只信任数据库中的 price,不信任客户端传入的任何金额字段。

"""

conn = get_connection()

try:

with conn: # commit / rollback

with conn.cursor() as cur:

# 1. read stock & price

cur.execute(

"""

SELECT price, stock

FROM products

WHERE id = %s

FOR UPDATE

""",

(request.product_id,),

)

prod_row = cur.fetchone()

if prod_row is None:

context.abort(grpc.StatusCode.NOT_FOUND, "product not found")

price, stock = prod_row # price: NUMERIC -> Decimal, stock: int

# 2. check quantity

qty = int(request.quantity)

if qty <= 0 or qty > 3:

context.abort(

grpc.StatusCode.INVALID_ARGUMENT,

"quantity must be between 1 and 3",

)

if stock < qty:

context.abort(

grpc.StatusCode.FAILED_PRECONDITION,

"not enough stock",

)

# 3. price, Decimal

if not isinstance(price, Decimal):

price = Decimal(str(price))

total_price = price * Decimal(qty)

# 4. insert

cur.execute(

"""

INSERT INTO orders (user_id, product_id, quantity, total_price)

VALUES (%s, %s, %s, %s)

RETURNING id, user_id, product_id, quantity, total_price, created_at

""",

(

request.user_id,

request.product_id,

qty,

total_price,

),

)

order_row = cur.fetchone()

if order_row is None:

context.abort(

grpc.StatusCode.INTERNAL,

"failed to create order",

)

# 5. minus stock

cur.execute(

"""

UPDATE products

SET stock = stock - %s

WHERE id = %s

""",

(qty, request.product_id),

)

# return

return row_to_order(order_row)

except Exception as e:

conn.rollback()

finally:

release_connection(conn)gRPC with API Service

gRPC provide all the CRUD service to Flask API Service:

service DbService {

// Products

rpc CreateProduct(CreateProductRequest) returns (Product);

rpc GetProduct(GetProductRequest) returns (Product);

rpc ListProducts(ListProductsRequest) returns (ListProductsResponse);

rpc UpdateProduct(UpdateProductRequest) returns (Product);

rpc DeleteProduct(DeleteProductRequest) returns (google.protobuf.Empty);

// Users

rpc CreateUser(CreateUserRequest) returns (User);

rpc GetUserById(GetUserByIdRequest) returns (User);

rpc GetUserBySid(GetUserBySidRequest) returns (User);

rpc GetUserByUsername(GetUserByUsernameRequest) returns (User);

rpc ListUsers(ListUsersRequest) returns (ListUsersResponse);

rpc UpdateUser(UpdateUserRequest) returns (User);

rpc DeleteUser(DeleteUserRequest) returns (google.protobuf.Empty);

// Orders

rpc CreateOrder(CreateOrderRequest) returns (Order);

rpc GetOrder(GetOrderRequest) returns (Order);

rpc ListOrders(ListOrdersRequest) returns (ListOrdersResponse);

rpc ListOrdersByUser(ListOrdersByUserRequest) returns (ListOrdersResponse);

rpc UpdateOrder(UpdateOrderRequest) returns (Order);

rpc DeleteOrder(DeleteOrderRequest) returns (google.protobuf.Empty);

}

Take Orders as an example:

message CreateOrderRequest {

int32 user_id = 1;

int32 product_id = 2;

int32 quantity = 3;

// price is calculated by Database

}

message GetOrderRequest {

int32 id = 1;

}

message ListOrdersRequest {

int32 page = 1;

int32 page_size = 2;

}

message ListOrdersByUserRequest {

int32 user_id = 1;

int32 page = 2;

int32 page_size = 3;

}

message ListOrdersResponse {

repeated Order orders = 1;

int32 page = 2;

int32 page_size = 3;

int32 total_count = 4;

}

message UpdateOrderRequest {

int32 id = 1;

int32 quantity = 2;

}

message DeleteOrderRequest {

int32 id = 1;

}Generating the gRPC code with grpc tools:

python -m grpc_tools.protoc \

-I. \

--python_out=. \

--grpc_python_out=. \

db.proto logging.protoThe file will help communication. We use this code to test gRPC connection:

import grpc

import db_pb2 # two files generated by protoc

import db_pb2_grpc # two files generated by protoc

def main():

channel = grpc.insecure_channel("localhost:50051")

stub = db_pb2_grpc.DbServiceStub(channel)

user = stub.CreateUser(

db_pb2.CreateUserRequest(

sid="12212345",

username="haibin",

email="laihb2022@mail.sustech.edu.cn",

password_hash="dummy_hash", # create a user

)

)

print("Created user:", user)Then every code is used to connect gRPC like this template.

OpenAPI Server + gRPC with DB Server

Take Orders_id_get as an example:

def orders_id_get(id_, token_info=None):

"""Get a single order by id."""

order_id = id_

stub = _get_db_stub()

try:

req = db_pb2.GetOrderRequest(id=order_id)

order_msg = stub.GetOrder(req)

return _success("Order fetched", order_to_dict(order_msg), 200)

except grpc.RpcError as e:

if e.code() == grpc.StatusCode.NOT_FOUND:

logging_client.send_logs([{

"service_name": "api-service/orders",

"level": "WARNING",

"path": connexion.request.path,

"method": connexion.request.method,

"user_sid": "",

"message": "Order not found"

}])

return _error("Order not found", 404)

logging_client.send_logs([{

"service_name": "api-service/orders",

"level": "ERROR",

"path": connexion.request.path,

"method": connexion.request.method,

"user_sid": "",

"message": f"DB service error: {e.code().name} - {e.details()}"

}])

return _error(

f"DB service error: {e.code().name} - {e.details()}",

502,

)This handler is a good example of how my OpenAPI-based API Service integrates JWT auth, gRPC, and centralized logging in a layered way:

-

REST + OpenAPI layer

orders_id_getis the controller forGET /orders/{id}generated from my OpenAPI spec.

Theid_parameter comes from the path, andtoken_infois injected by the JWT bearerAuth security handler. That means:- The JWT is validated before this function runs.

- On success, decoded claims (e.g.

sid,user_id) are available viatoken_info, even though this particular endpoint doesn’t yet enforce per-user ownership.

-

gRPC DB Service layer

Instead of talking to PostgreSQL directly, the API calls the DB Service via gRPC:_get_db_stub()returns a gRPC stub for the DB Service.- The handler builds a strongly-typed

GetOrderRequest(db_pb2.GetOrderRequest(id=order_id)) and callsstub.GetOrder(req). - On success, the protobuf

order_msgis converted into a plain dict withorder_to_dict(order_msg)and wrapped by_success("Order fetched", ..., 200)as a JSON HTTP 200 response. - This cleanly separates HTTP/JSON concerns (API Service) from SQL/connection-pooling concerns (DB Service).

-

Error mapping and service “tiering”

gRPC status codes from the DB Service are mapped to appropriate HTTP responses at the API tier:- If

e.code() == grpc.StatusCode.NOT_FOUND, the API returns an HTTP 404"Order not found". - Any other gRPC error is treated as an internal backend failure and returned as HTTP 502

"DB service error: …". - This keeps the REST interface stable while the DB tier is an internal implementation detail.

- If

-

Centralized structured logging via Logging Service + Kafka

On every failure, the handler sends a structured log to the Logging Service client:- Fields include

service_name("api-service/orders"), loglevel("WARNING"or"ERROR"), HTTPpath,method, and a human-readablemessage. - These logs are streamed via gRPC to the Logging Service, which then forwards them into Kafka, so an administrator can monitor failed

get-ordercalls centrally. - The

user_sidfield is already reserved; once I plug intoken_info, I can attach the authenticated user’s SID to each log entry.

- Fields include

Overall, this endpoint shows my backend design goals:

- JWT-protected OpenAPI REST layer (with

token_infoplumbed in), - A middle gRPC tier (DB Service) that encapsulates all database logic and error codes, outputing

status codeanddetail message, - A separate Logging Service that receives structured logs from the API Service and forwards them to Kafka for monitoring.

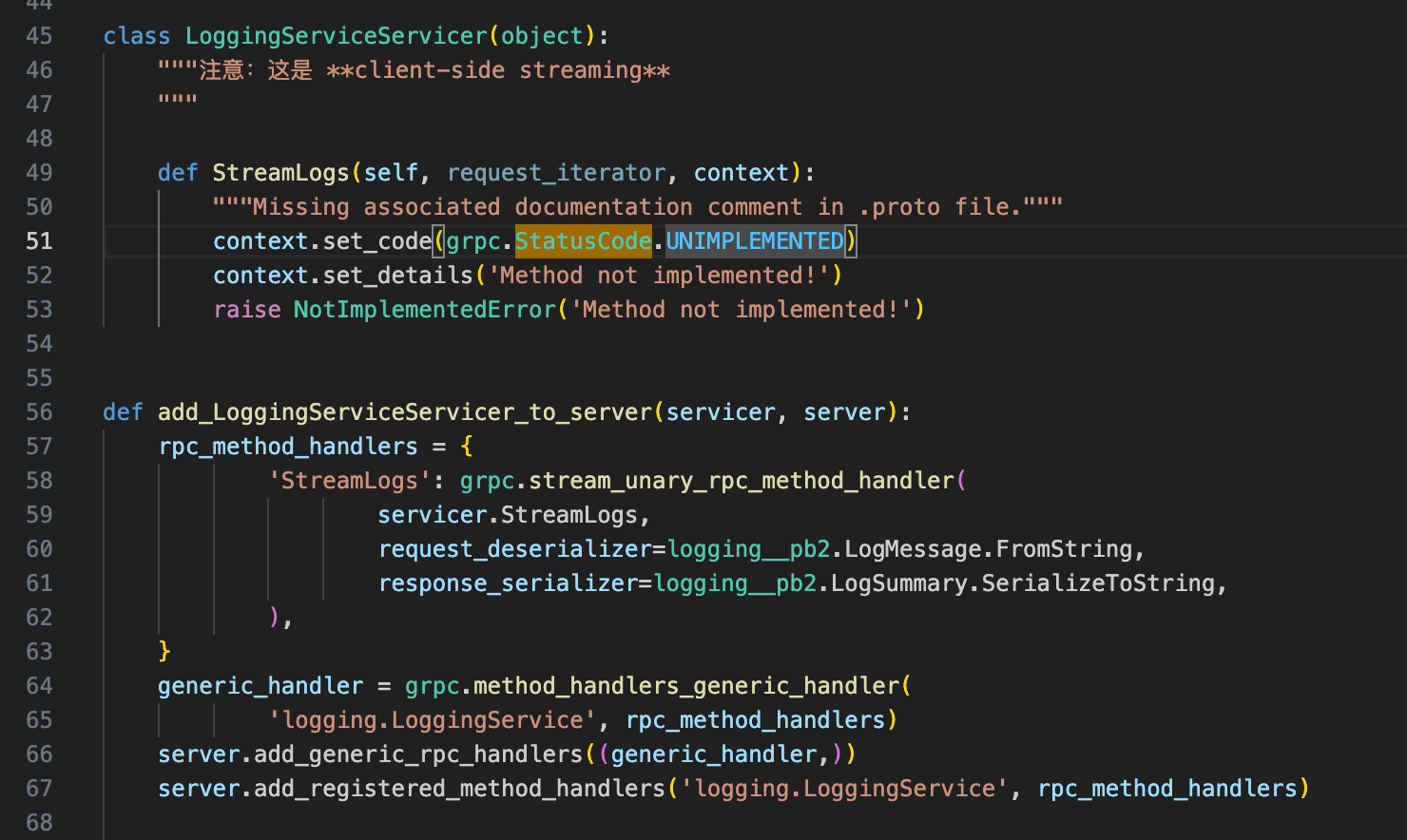

Logging Service + gRPC

- write the code for logs

Then use gRPC to communicate.

syntax = "proto3";

package logging;

option go_package = "loggingpb";

message LogMessage {

string service_name = 1; // "api-service" / "db-service" 等

string level = 2; // "INFO" / "WARN" / "ERROR"

string path = 3; // 请求路径,比如 "/users/login"

string method = 4; // "GET" / "POST"

string user_sid = 5; // 可选:当前用户 SID

string message = 6; // 文本日志,比如 "User login success"

int64 timestamp_ms = 7; // 客户端填:毫秒级 Unix 时间戳

}

message LogSummary {

int64 count = 1; // num of logs

}

// **client-side streaming**

service LoggingService {

rpc StreamLogs (stream LogMessage) returns (LogSummary);

}send_logs is the function we use in all the API Service.

def send_logs(logs):

"""

logs: List[dict],example:

{

"service_name": "api-service",

"level": "INFO",

"path": "/users/login",

"method": "POST",

"user_sid": "123",

"message": "login ok"

}

"""

stub = get_logging_stub()

INSTANCE_NAME = os.getenv("INSTANCE_NAME", "unknown")

def gen():

for log in logs:

yield logging_pb2.LogMessage(

service_name=INSTANCE_NAME,

level=log.get("level", "INFO"),

path=log.get("path", ""),

method=log.get("method", ""),

user_sid=log.get("user_sid", ""),

message=log.get("message", ""),

timestamp_ms=int(time.time() * 1000)

)

return stub.StreamLogs(gen())Then the API Service can use:

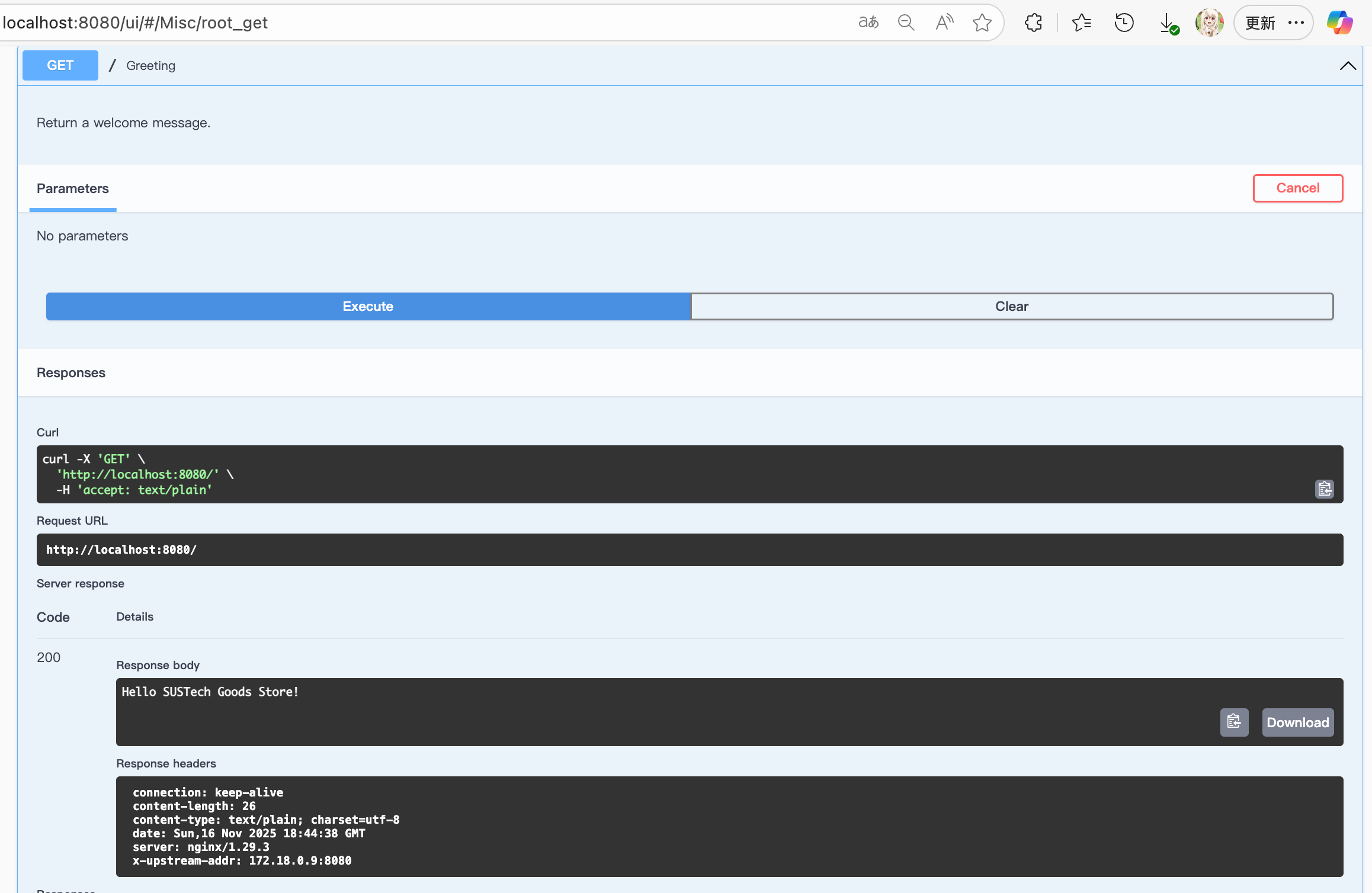

def root_get(): # noqa: E501

"""Greeting

Return a welcome message. # noqa: E501

:rtype: Union[str, Tuple[str, int], Tuple[str, int, Dict[str, str]]

"""

logging_client.send_logs([{

"service_name": "api-service/misc",

"level": "INFO",

"path": "/",

"method": "GET",

"user_sid": "",

"message": "Root endpoint accessed"

}])

return 'Hello SUSTech Goods Store!'

you can also observe the load imbalance here (The api1 and api2 are two API Server in docker network)

Docker Compose Network

Connect everything in the docker

##### YOUR SERVICES GO BELOW THIS LINE #####

db_service:

build: ./src/db_service

container_name: db_service

depends_on:

- postgres

environment:

POSTGRES_DSN: "dbname=goodsstore user=dncc password=dncc host=postgres port=5432"

# ---------- API 副本 ----------

api1:

build:

context: ./src/api_service/server/python-flask/

container_name: api1

env_file:

- .env

environment:

- LOGGING_ADDR=logging_service:50052

- INSTANCE_NAME=api1

- DB_ADDR=db_service:50051

ports: [] # 不再直接映射到宿主机端口,由 nginx 代理

depends_on:

- db_service

- logging_service

api2:

build:

context: ./src/api_service/server/python-flask/

container_name: api2

env_file:

- .env

environment:

- INSTANCE_NAME=api2

- LOGGING_ADDR=logging_service:50052

- DB_ADDR=db_service:50051

ports: []

depends_on:

- db_service

- logging_service

# ---------- NGINX ----------

nginx:

image: nginx:alpine

container_name: nginx_lb

depends_on:

- api1

- api2

ports:

- "8080:80" # http://localhost:8080 -> NGINX

volumes:

- ./nginx.conf:/etc/nginx/nginx.conf:ro

networks:

- default

logging_service:

build:

context: ./src/logging_service

dockerfile: Dockerfile

container_name: logging_service

hostname: logging_service

depends_on:

- kafka

environment:

- KAFKA_BOOTSTRAP_SERVERS=kafka:9092

- KAFKA_TOPIC=api-logs

# gRPC internel

ports:

- "50052:50052"

networks:

- default

volumes:

pg_data: # A placeholder volume without any configuration4. API Design

In this section, I will show the API Design and authentication logic.

We have 3 kinds of api in the service:

- Greeting and See products API: the API to check the website.

- User accounts API: the API for user accounts like login, delete and update profile.

- Orders API: the API to check and order users' orders.

All of the api are shown here:

At the base URL, user can find a greeting API that returns a welcome message. And they can check the products without any password or JWT.

| RESTful API | Method | Description | Need Passwd? | Need JWT? | Return |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| / | GET | Greeting | ❌ | ❌ | "Hello!" |

| /products | GET | List products | ❌ | ❌ | All Products |

| /products/{id} | GET | Get product | ❌ | ❌ | Product |

All of them don't need authentication, since they should be the goods and page that show to everyone that visit the online shop.

A product information contains:

| Feature | Data type |

|---|---|

id |

key int |

Name |

string |

Description |

string |

Category |

string |

price |

string |

slogan |

string |

stock |

int |

created_at |

time |

Note: here in design, we should use string or decimal to design price tag. The OpenAPI only have string, so we design it into string. And in database, we use decimal to calculate the total price:

from decimal import Decimal

price = Decimal(row.price) # DB → Decimal

qty = Decimal(request.quantity)

total = price * qty To place orders, the client have to register an account in the system. The following API can help them deal with their account information with register, login, getting profile, update profile and delete account:

| RESTful API | Method | Description | Need Passwd? | Need JWT? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| /users/register | POST | Register | ✅ | ❌ |

| /users/login | POST | Login | ✅ | ❌ (login will generate JWT) |

| /users/me | GET | Get my profile | ❌ | ✅ |

| /users/me | PATCH | Update my profile | ❌ | ✅ |

| /users/me | DELETE | Delete an account | ❌ | ✅ |

The getting profile, updating profile and deleting account needs JWT to authentication. And Login & Register need password.

Every user can see their Profile info :

| User | Data type | Can be seen? | Changeable? |

|---|---|---|---|

id |

int | ✅ | ❌ |

username |

string | ✅ | ✅ |

email |

string | ✅ | ✅ |

sid |

string | ✅ | ❌ |

created_at |

time | ✅ | ❌ |

password |

string | ❌ | ✅(Change hash in db) |

The password will be encrypted with hash when sending to database:

password_hash = hashlib.sha256(password.encode("utf-8")).hexdigest()

try:

req = db_pb2.CreateUserRequest(

sid=sid,

username=username,

email=email,

password_hash=password_hash,

)

user = stub.CreateUser(req)So that the db won't leak user's password.

And this is the input and return for the user api:

| RESTful API | Method | Description | Must input | Can be null | Return |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /users/register | POST | Register | sid, password |

username, email |

SUCCESS/FAIL |

| /users/login | POST | Login | sid, password |

- | SUCCESS/FAIL |

| /users/me | GET | Get my profile | JWT | - | Profile info |

| /users/me | PATCH | Update my profile | JWT, your update things | - | SUCCESS/FAIL |

| /users/me | DELETE | Delete an account | JWT | - | SUCCESS/FAIL |

After having a complete account, they can place orders, check their own orders and delete one of their orders by using the following API:

| RESTful API | Method | Description | Need Passwd? | Need JWT? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| /orders | POST | Place an order | ❌ | ✅ |

| /orders/{id} | GET | Check your own order with id | ❌ | ✅ |

| /orders | GET | Check all your own orders | ❌ | ✅ |

| /orders/{id} | DELETE | Cancel an order | ❌ | ✅ |

| Product | Data type | Can be seen? |

|---|---|---|

id |

int | ✅ |

userid |

int | ✅ |

product_id |

int | ✅ |

quantity |

int | ✅ |

created_at |

time | ✅ |

total_price |

string | ✅ |

| RESTful API | Method | Description | Must input | Return |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| /orders | POST | Place an order | product_id, quantity |

total_price, created_at |

| /orders/{id} | GET | Check order with id | id, JWT |

Your Order info |

| /orders/ | GET | Check all your order | JWT | Your Orders info |

| /orders/{id} | DELETE | Cancel an order | JWT | SUCCESS/FAIL |

Generate:

docker run --rm \

-v ${PWD}:/local \

openapitools/openapi-generator-cli:v7.8.0 generate \

-i /local/openapi.yaml \

-g python-flask \

-o /local/server/python-flaskIn my API Service, all “user-specific” operations require authentication, while read-only “public” operations don’t.

4.1 Which APIs require authentication?

No authentication required (public):

GET /– Greeting APIGET /products– List all productsGET /products/{id}– Get product detailsPOST /users/register– Create a new user accountPOST /users/login– User login, returns a JWT

Authentication required (JWT Bearer):

- User APIs

GET /users/me– Get the current user’s profileGET /users/{id}– Get a specific user (only if it’s the same as the logged-in user)PUT /users/{id}– Update user infoDELETE /users/{id}– Deactivate user

- Order APIs

POST /orders– Place a new order (place-order)GET /orders/{id}– Get order details (only owner can see it)DELETE /orders/{id}– Cancel an order

In the OpenAPI YAML, these operations are marked with a security section using a bearerAuth security scheme, so Swagger UI, connexion, etc. know they require a token.

4.2 How I implement the authentication logic

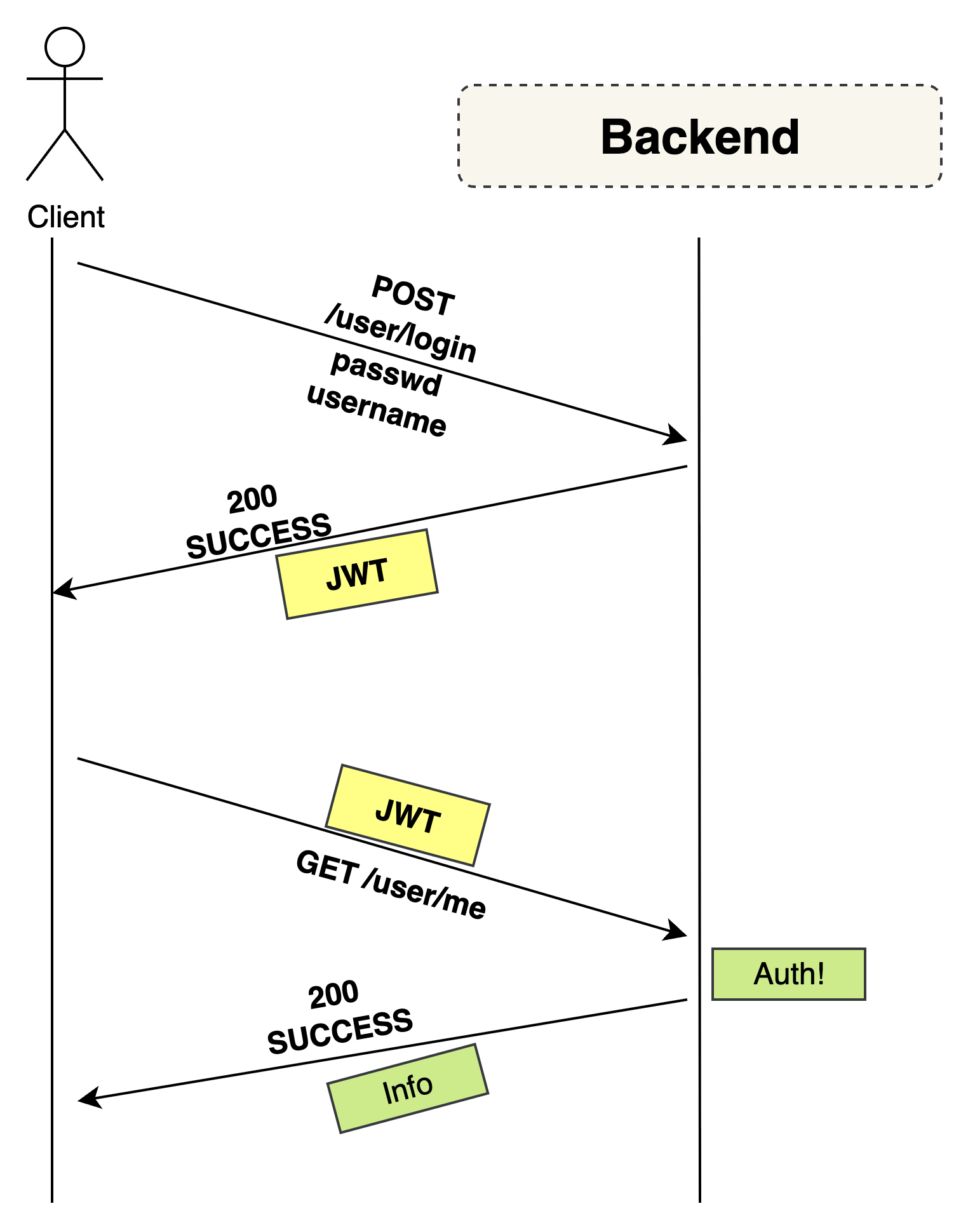

To create a JWT, clients first call the POST /users/login API with a username and password. The API Service uses gRPC to query the DB Service for the user record and verifies the password against a stored hash. On success, the API Service issues a JWT signed with a secret key loaded from the environment. The JWT payload contains the user’s sid, user_id, and an expiration timestamp.

In our API service, user-specific operations such as fetching the current user profile (GET /users/me), updating/deactivating the current user, and creating / listing / cancelling orders are protected by JWT-based authentication.

For subsequent requests, the client includes this token in the Authorization: Bearer <token> HTTP header. The API Service validates the token on each protected endpoint by verifying its signature and expiration. It then extracts the sid from the payload and calls the DB Service (e.g., GetUserBySid) to retrieve the authoritative user record and user_id. All downstream gRPC calls use this user_id instead of trusting any client-supplied identifier, so users can only access their own orders or profile. Additionally, every login and order-related request is logged via a client-side streaming gRPC connection to the Logging Service, which forwards all log messages to a Kafka topic for centralized monitoring.

4.2.1. Security scheme in OpenAPI

In the OpenAPI spec I define a JWT bearer scheme:

components:

securitySchemes:

bearerAuth:

type: http

scheme: bearer

bearerFormat: JWTThen for each protected operation:

paths:

/orders:

post:

security:

- bearerAuth: []

...

/users/me:

get:

security:

- bearerAuth: []

...This tells connexion to call my info_from_bearerAuth function for these APIs.

4.2.2. Issuing the JWT on login

When the client calls POST /users/login with email/password:

- API Service calls the DB Service via gRPC to fetch the user by id

- It verifies the password against the stored hash.

- If valid, it creates a JWT, for example:

import jwt

from datetime import datetime, timedelta

JWT_SECRET = os.getenv("JWT_SECRET", "dev_secret")

JWT_ALG = "HS256"

JWT_EXPIRE_HOURS = 12

def _create_jwt_for_user(u: db_pb2.User) -> str:

now = datetime.now(timezone.utc)

payload = {

"sid": u.sid,

"user_id": u.id,

"iat": int(now.timestamp()),

"exp": int((now + timedelta(hours=JWT_EXPIRE_HOURS)).timestamp()),

}

token = pyjwt.encode(payload, JWT_SECRET, algorithm=JWT_ALGO)

# PyJWT>=2 return str

return token- The login API returns:

The client then sends this token in the Authorization HTTP header:

Authorization: Bearer <JWT>.

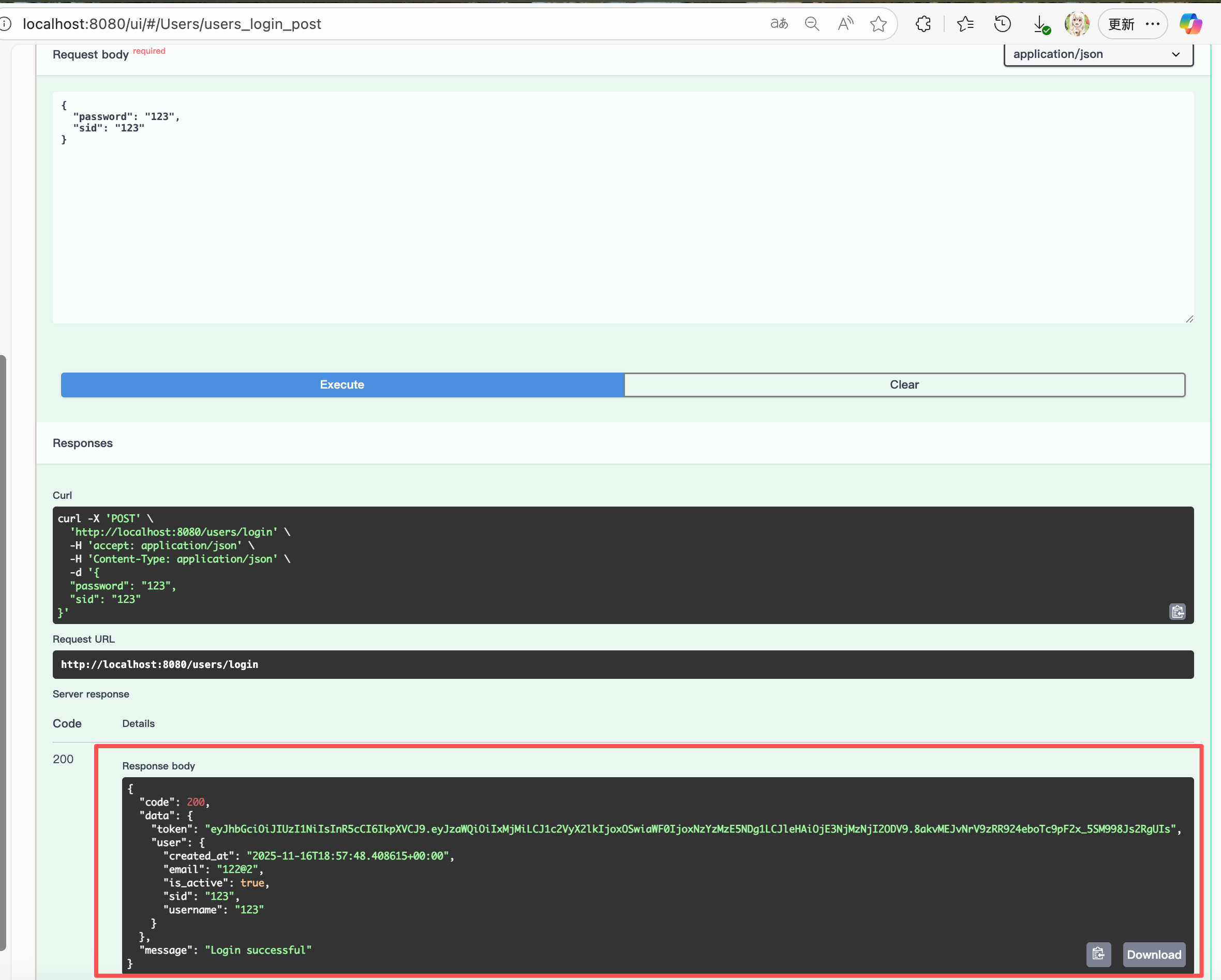

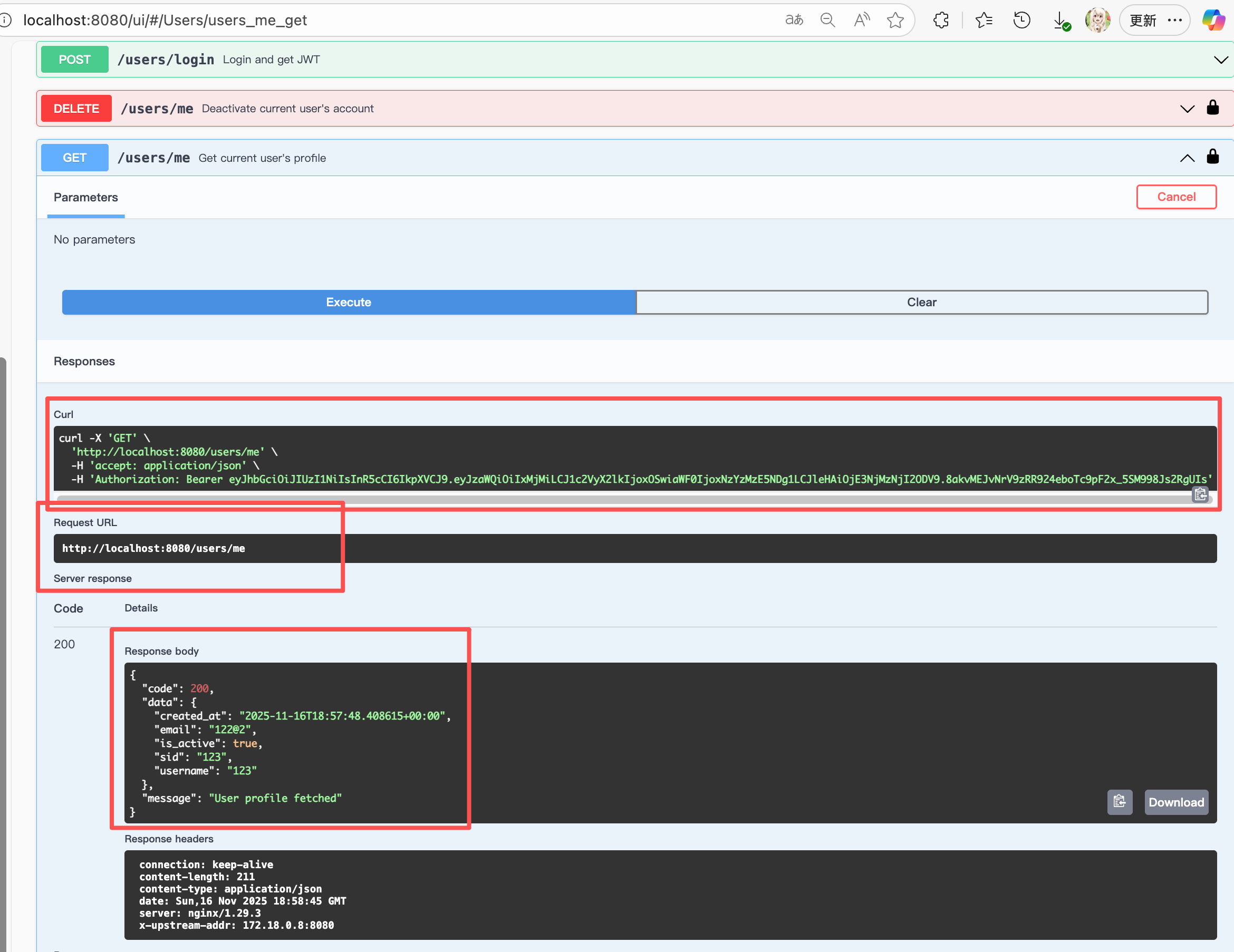

And they can get the account info:

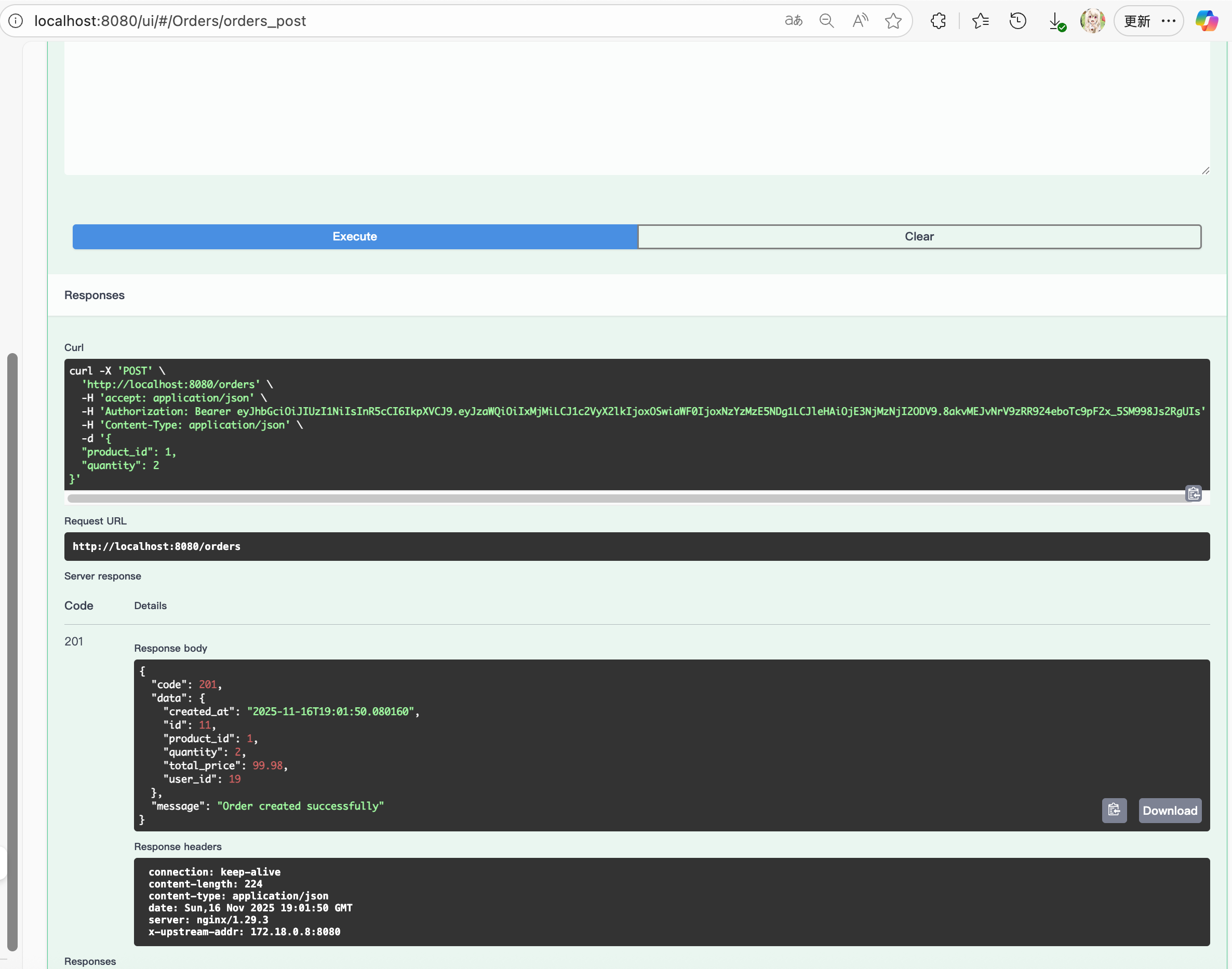

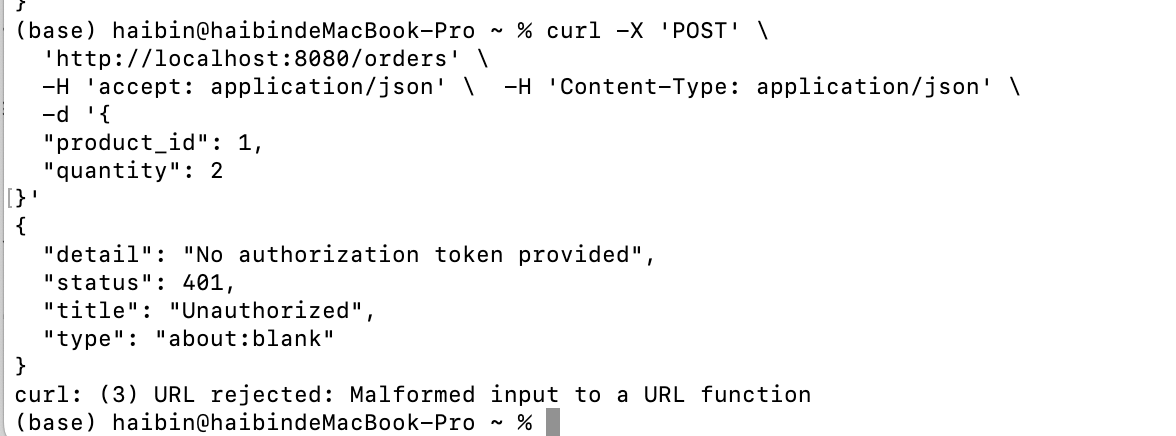

They can also use this JWT to post orders (password is not needed here due to safety)

4.2.3. Decoding & validating the token on each protected API

Connexion calls info_from_bearerAuth(token) for any operation that requires bearerAuth. My implementation roughly looks like:

import jwt

from jwt import ExpiredSignatureError, InvalidTokenError

from openapi_server.models.error_response import ErrorResponse

JWT_SECRET = os.getenv("JWT_SECRET", "dev_secret")

JWT_ALG = "HS256"

def info_from_bearerAuth(token: str):

"""

Check and retrieve authentication information from custom bearer token.

Returned value will be passed in 'token_info' parameter of your operation function, if there is one.

'sub' or 'uid' will be set in 'user' parameter of your operation function, if there is one.

:param token: Token provided by Authorization header (without 'Bearer ')

:type token: str

:return: Decoded token information or None if token is invalid

:rtype: dict | None

"""

try:

# 解 JWT,验证签名和 exp

payload = jwt.decode(token, JWT_SECRET, algorithms=[JWT_ALGORITHM])

# 你登录生成里放了 sid 和 user_id,这里直接返回整个 payload

return payload

except ExpiredSignatureError:

# 过期

print("[JWT] Token expired")

return None

except InvalidTokenError as e:

# 签名错误 / 格式错误 / 算法不对等都进这里

print(f"[JWT] Invalid token: {e}")

return NoneNow, the controller functions can accept token_info:

def users_me_get() -> Tuple[Dict, int]:

"""

获取当前登录用户信息:

- 从 JWT 拿 user_id 或 sid

- 再调 gRPC GetUserBySid / GetUserById

"""

payload, err = _get_current_user_payload()

if err is not None:

return err

stub = _get_db_stub()

sid = payload.get("sid")

try:

req = db_pb2.GetUserBySidRequest(sid=sid)

user = stub.GetUserBySid(req)

except grpc.RpcError as e:

if e.code() == grpc.StatusCode.NOT_FOUND:

logging_client.send_logs([{

"service_name": "api-service/user",

"level": "WARNING",

"path": connexion.request.path,

"method": connexion.request.method,

"user_sid": sid or "",

"message": "User not found"

}])

return _error("User not found", 404)

logging_client.send_logs([{

"service_name": "api-service/user",

"level": "ERROR",

"path": connexion.request.path,

"method": connexion.request.method,

"user_sid": sid or "",

"message": f"DB service error: {e.code().name} - {e.details()}"

}])

return _error(f"DB service error: {e.code().name} - {e.details()}", 502)

logging_client.send_logs([{

"service_name": "api-service/user",

"level": "INFO",

"path": connexion.request.path,

"method": connexion.request.method,

"user_sid": sid,

"message": "User profile fetched successfully"

}])

return _success("User profile fetched", _grpc_user_to_profile(user), 200)So authentication is: “verify JWT, extract user info”.

And I also add a simple authorization check: the user_id in the token must match the resource’s owner (order.user_id, user.id, etc.).

4.2.4. Error behavior

-

If the Authorization header is missing, malformed, or the token is invalid/expired,

the API returns 401 Unauthorized with a JSON error body.

-

If the token is valid, but the user tries to access another user’s data / order, the API returns 403 Forbidden.

-

Other code for different reasons as shown above (404, 502 etc).

So in summary:

- I expose a public subset of APIs (greeting, product browsing, register, login).

- All user-specific operations and order operations are protected with JWT bearer authentication (

bearerAuthin OpenAPI). - The auth logic is implemented via PyJWT + an

info_from_bearerAuthhook in connexion: login issues a signed, expiring JWT; each protected call decodes the token, checks expiry, and then uses the embeddeduser_id/sidto fetch data from the DB Service and enforce ownership.

5. Field Data types

This section shows how I select data types. Mostly I decide them base on database data type. And we show our principle and an example of product.

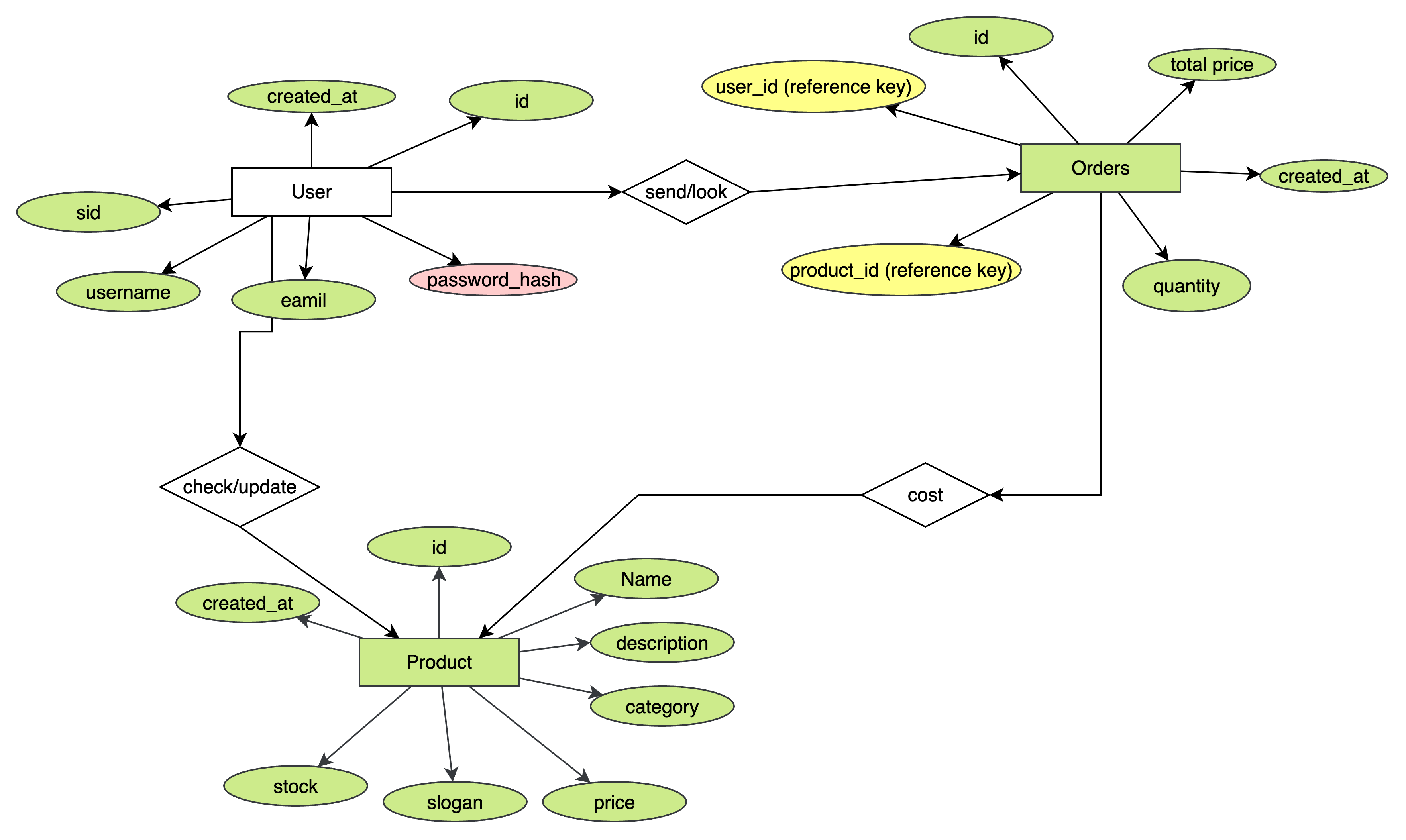

First, I drew an E-R graph for the DB:

This is the most important part that I get understand the whole structure. By understanding the relationship, we can choose and select the data type with full consideration.

📌 General Selection Principles

1. Use database-native types first

PostgreSQL has rich numeric and timestamp types, so DB types are chosen based on data characteristics.

2. Choose Protobuf types that safely map to DB types

Protobuf has fewer scalar types; for example:

- No decimal → use

stringorint64scaled representation - No datetime → use

google.protobuf.Timestamp

3. OpenAPI must match the Proto type semantics

While JSON has limited primitives, it must align with Protobuf encoding.

Example: Products

| Feature | Data type |

|---|---|

id |

key int |

Name |

string |

Description |

string |

Category |

string |

price |

string/Decimal |

slogan |

string |

stock |

int |

created_at |

time |

We store product in DB as a table:

CREATE TABLE products (

id SERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

name VARCHAR(100) NOT NULL,

description TEXT,

category VARCHAR(50),

price DECIMAL(10, 2) NOT NULL,

slogan VARCHAR(255),

stock INT NOT NULL DEFAULT 500,

created_at TIMESTAMP DEFAULT NOW()

);Then for gRPC proto:

message Product {

int32 id = 1;

string name = 2;

string description = 3;

string category = 4;

string price = 5;

string slogan = 6;

int32 stock = 7;

google.protobuf.Timestamp created_at = 8;

}int32foridandstock→ safe match with PostgreSQLINTEGERstring price→ because protobuf has no decimal type- Using

stringprevents rounding errors - Matches what psycopg2 returns for NUMERIC

- Using

As for OpenAPI, we also use similar data type, so that OpenAPI can collaborate with gRPC very well.

Product:

type: object

properties:

id:

type: integer

example: 1

name:

type: string

example: "Laptop"

description:

type: string

example: "A powerful laptop"

category:

type: string

example: "Electronics"

price:

type: string

example: "999.99"

slogan:

type: string

example: "Fast and Light"

stock:

type: integer

example: 10

created_at:

type: string

format: date-time

example: "2025-11-13T12:00:00Z"

required:

- id

- name

- price

- stock

- created_atThis is a simple summary of our example.

| Field | PostgreSQL Type | Proto Type | OpenAPI Type | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|

id |

SERIAL / INTEGER |

int32 |

integer(int32) |

Simple numeric key |

name |

TEXT |

string |

string |

Textual data |

category |

TEXT |

string |

string |

Textual data |

price |

NUMERIC(10,2) |

string |

string |

Avoids float precision loss |

stock |

INTEGER |

int32 |

integer(int32) |

Integer count |

6. gRPC verification

In this section we try to do gRPC verification just like things in our lab.

We try to print out the Hex strings:

try:

resp = stub.ListProducts(req)

except:

pass

# print out resp as gRPC message for debugging

res2 = resp.SerializeToString()

print(resp, flush=True)

print(res2, flush=True)

import binascii

hex_str = binascii.hexlify(res2).decode("ascii")

print("Hexadecimal representation of the gRPC response:", flush=True)

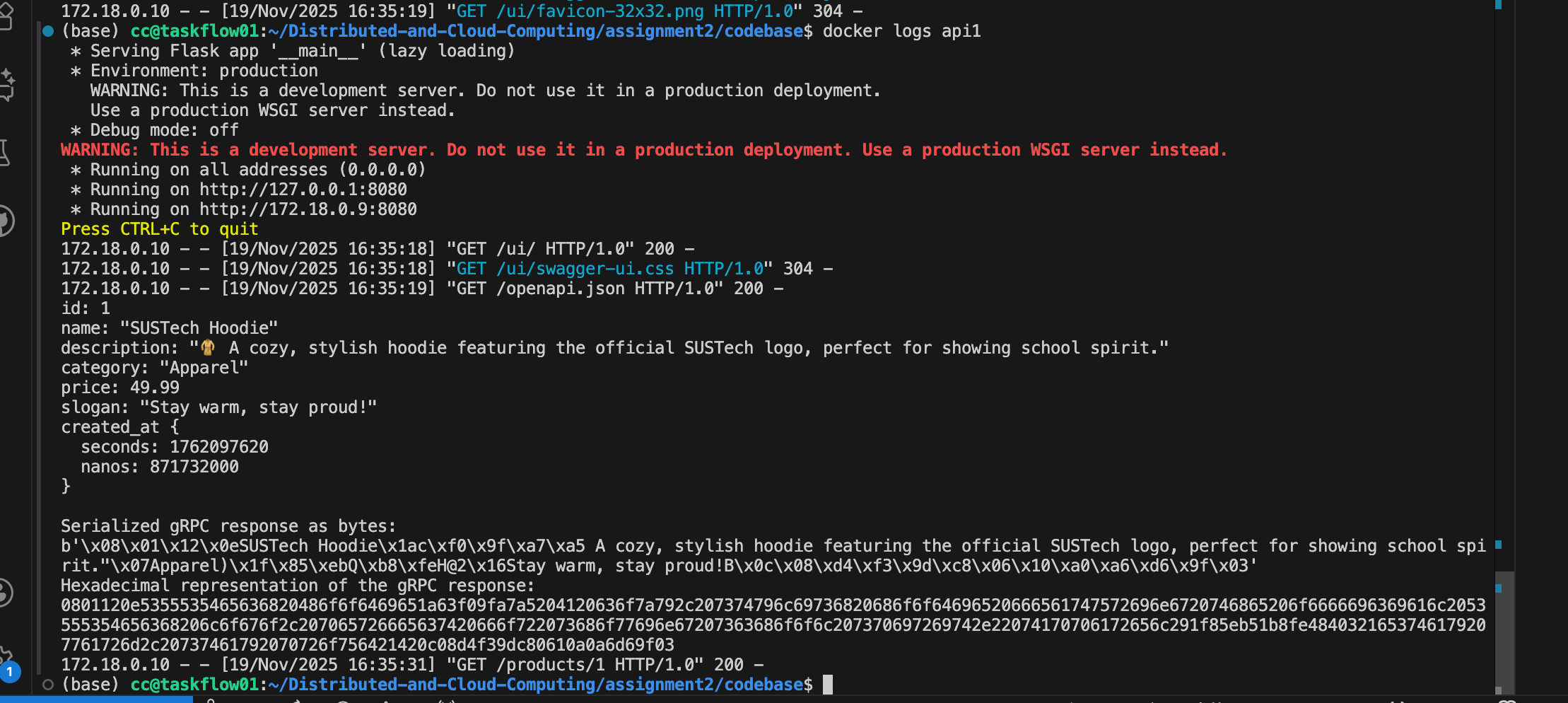

print(hex_str, flush=True)Here is the code:

So this is our message, and our encrypted code:

id: 1

name: "SUSTech Hoodie"

description: "🧥 A cozy, stylish hoodie featuring the official SUSTech logo, perfect for showing school spirit."

category: "Apparel"

price: 49.99

slogan: "Stay warm, stay proud!"

created_at {

seconds: 1762097620

nanos: 871732000

}JSON length: 289

Serialized gRPC response as bytes:

b'\x08\x01\x12\x0eSUSTech Hoodie\x1ac\xf0\x9f\xa7\xa5 A cozy, stylish hoodie featuring the official SUSTech logo, perfect for showing school spirit."\x07Apparel)\x1f\x85\xebQ\xb8\xfeH@2\x16Stay warm, stay proud!B\x0c\x08\xd4\xf3\x9d\xc8\x06\x10\xa0\xa6\xd6\x9f\x03'Hexadecimal representation of the gRPC response:

0801120e5355535465636820486f6f6469651a63f09fa7a5204120636f7a792c207374796c69736820686f6f64696520666561747572696e6720746865206f6666696369616c2053555354656368206c6f676f2c207065726665637420666f722073686f77696e67207363686f6f6c207370697269742e22074170706172656c291f85eb51b8fe4840321653746179207761726d2c20737461792070726f756421420c08d4f39dc80610a0a6d69f03That's 175 byte

--- Size Comparison ---

Protobuf : 175 bytes

JSON : 289 bytes

Ratio : 0.606

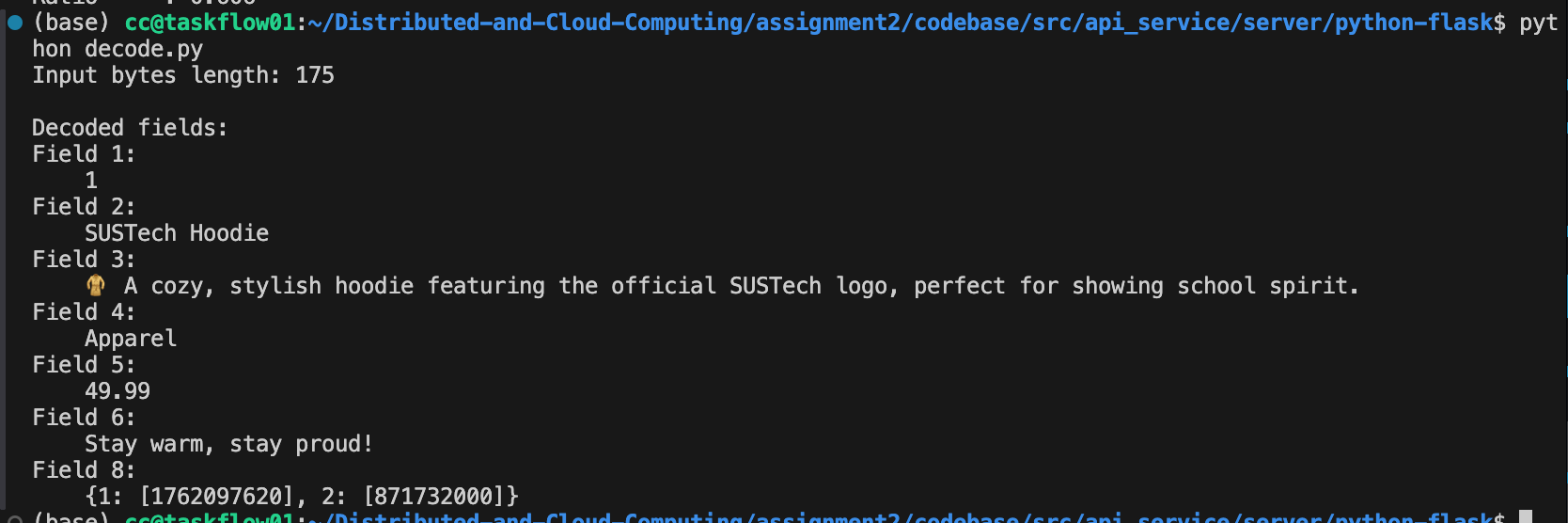

We can use following code to generate decode result:

import binascii

# ------------------------------

# Wire type constants

# ------------------------------

WIRE_VARINT = 0

WIRE_64BIT = 1

WIRE_LENGTH_DELIMITED = 2

# ------------------------------

# Helper: decode a varint

# ------------------------------

def read_varint(buffer, index):

shift = 0

result = 0

while True:

b = buffer[index]

index += 1

result |= (b & 0x7F) << shift

if not (b & 0x80):

break

shift += 7

return result, index

# ------------------------------

# Helper: decode 64-bit (double)

# ------------------------------

import struct

def read_64bit(buffer, index):

data = buffer[index:index+8]

value = struct.unpack("<d", data)[0] # little-endian double

return value, index + 8

# ------------------------------

# Helper: recursively decode a nested message

# ------------------------------

def parse_message(buffer, index, end):

fields = {}

while index < end:

# Decode tag

tag, index = read_varint(buffer, index)

field_number = tag >> 3

wire_type = tag & 0x07

# Decode by wire type

if wire_type == WIRE_VARINT:

value, index = read_varint(buffer, index)

elif wire_type == WIRE_64BIT:

value, index = read_64bit(buffer, index)

elif wire_type == WIRE_LENGTH_DELIMITED:

length, index = read_varint(buffer, index)

value_bytes = buffer[index:index+length]

index += length

# Try nested message parse

# For Timestamp and strings

try:

# Attempt nested decode

nested = parse_message(value_bytes, 0, len(value_bytes))

value = nested

except Exception:

# Otherwise it's string

value = value_bytes.decode("utf-8")

else:

raise Exception(f"Unsupported wire type: {wire_type}")

# Store field

fields.setdefault(field_number, []).append(value)

return fields

# ------------------------------

# Manual ParseFromString

# ------------------------------

def manual_parse(hex_data):

raw = binascii.unhexlify(hex_data)

print(f"Input bytes length: {len(raw)}")

decoded = parse_message(raw, 0, len(raw))

return decoded

# ------------------------------

# Test with your data

# ------------------------------

if __name__ == "__main__":

hex_data = (

"0801120e5355535465636820486f6f6469651a63f09fa7a5204120636f7a792c2073"

"74796c69736820686f6f64696520666561747572696e6720746865206f6666696369"

"616c2053555354656368206c6f676f2c207065726665637420666f722073686f7769"

"6e67207363686f6f6c207370697269742e22074170706172656c291f85eb51b8fe48"

"40321653746179207761726d2c20737461792070726f756421420c08d4f39dc80610"

"a0a6d69f03"

)

msg = manual_parse(hex_data)

print("\nDecoded fields:")

for field, values in msg.items():

print(f"Field {field}:")

for v in values:

print(" ", v)Then we can get the result:

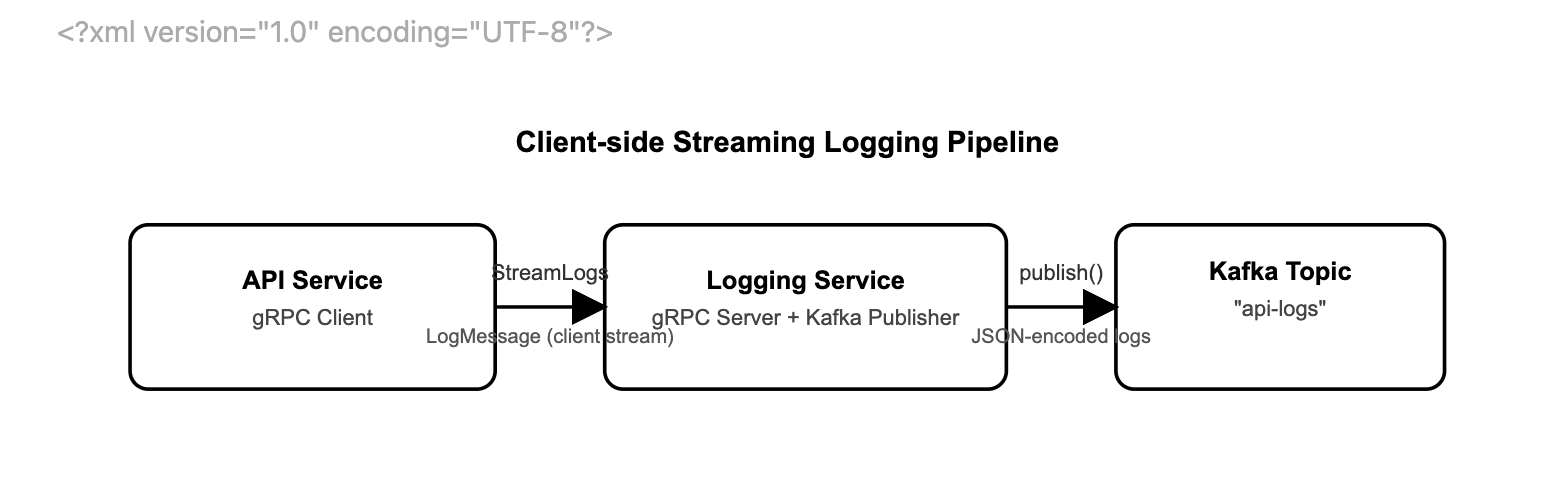

7. client-side streaming gRPC

This section we will introduce and explain how the client-side streaming RPC works in our Logging Service.

In our implementation, the Logging Service defines a client-side streaming RPC named StreamLogs. The RESTful API Service acts as the gRPC client and continuously sends log messages through a single streaming RPC call, while the Logging Service receives these messages and forwards them to Kafka.

During runtime, API Service will send StreamLogs to Logging Service, and it will publish them to Kafka. Then if no more logs, client closes stream. So by doing that we don't need to have every LogMessage with every connections since ,any log messages share a single gRPC connection.

1. Client Implementation (API Service)

On the client side, we implement a helper function send_logs(logs):

def send_logs(logs):

stub = get_logging_stub()

INSTANCE_NAME = os.getenv("INSTANCE_NAME", "unknown")

def gen():

for log in logs:

yield logging_pb2.LogMessage(

service_name=INSTANCE_NAME,

level=log.get("level", "INFO"),

path=log.get("path", ""),

method=log.get("method", ""),

user_sid=log.get("user_sid", ""),

message=log.get("message", ""),

timestamp_ms=int(time.time() * 1000)

)

return stub.StreamLogs(gen())Here:

get_logging_stub()creates (and reuses) a gRPC channel and aLoggingServiceStubbound toLOGGING_ADDR.send_logs(logs)takes a list of Python dictionaries representing log entries.- Inside

send_logs, we define a generator functiongen()that:- Iterates over the input list

logs. - Converts each dictionary into a

LogMessageprotobuf. - Uses

yieldto stream messages one by one.

- Iterates over the input list

We then call stub.StreamLogs(gen()). This passes the generator gen() as the request_iterator for the StreamLogs RPC. The RPC is client-side streaming: multiple LogMessage instances are sent over a single RPC call, and the server returns a LogSummary only after the stream is closed.

2. Server Implementation (Logging Service)

On the server side, we implement the LoggingService as follows:

class LoggingService(logging_pb2_grpc.LoggingServiceServicer):

def __init__(self, publisher):

self.publisher = publisher

def StreamLogs(self, request_iterator, context):

count = 0

for req in request_iterator:

payload = {

"service_name": req.service_name,

"level": req.level,

"path": req.path,

"method": req.method,

"user_sid": req.user_sid,

"message": req.message,

"timestamp_ms": req.timestamp_ms

}

try:

self.publisher.publish(

topic=KAFKA_TOPIC,

key=req.service_name.encode(),

value=json.dumps(payload).encode()

)

count += 1

except Exception as e:

LOGGER.error("Publish fail: %s", e)

LOGGER.info("Received %d logs", count)

return logging_pb2.LogSummary(count=count)Key points:

request_iteratoris the server-side view of the client stream. Each time the client’s generatorgen()yields aLogMessage, thefor req in request_iteratorloop receives it.- For each

LogMessage:- We convert it into a JSON payload.

- We call

self.publisher.publish(...)to send it to the Kafka topicapi-logs, using the service name as the message key. - We increment

countto track how many log entries were received in this stream.

- After the client finishes sending logs and closes the stream:

- The loop terminates.

- The server logs the total number of messages.

- The server returns a

LogSummary(count=count)back to the client, completing the RPC.

Summary of the Streaming Behavior

- Single RPC, multiple messages: The API Service opens one

StreamLogsRPC and streams multipleLogMessageobjects through it. - Streaming generator: On the client, a Python generator function (

gen()) produces the log messages lazily for the gRPC stream. - Incremental processing: On the server,

StreamLogsprocesses each incoming message immediately and publishes it to Kafka. - Final aggregation: After all log messages are sent, the server replies with a single

LogSummary, indicating how many logs were processed for this stream.

This design leverages gRPC client-side streaming to build an efficient, low-overhead logging pipeline from the API Service to Kafka via the Logging Service.

7. Docker & Docker Compose

In my implementation, I use a single Docker Compose setup so that all containers automatically join the same user-defined bridge network and can resolve each other by service name. PostgreSQL, Kafka, the DB Service, the Logging Service, and the RESTful API Service are all declared as services in docker-compose.yml.

Single Docker Compose network = shared “LAN”

- Each service is reachable by its service name as a hostname

db_service→ gRPC DB serverlogging_service→ gRPC logging serverkafka→ Kafka brokerpostgres→ PostgreSQLapi1,api2→ RESTful API instances- NGINX -> api1, api2

- No need to hard-code IPs; Docker provides internal DNS.

Configure DB Service ↔ PostgreSQL: port 5432

Configure API Service ↔ DB Service & Logging Service: port 50051 & 50052

Configure Logging Service ↔ Kafka: port 9092

Inside the network, I use service names as hostnames (e.g., postgres:5432, db_service:50051, logging_service:50052, kafka:9092). I pass these endpoints into the containers via environment variables such as DB_HOST=postgres, DB_ADDR=db_service:50051, and KAFKA_BOOTSTRAP_SERVERS=kafka:9092.

The API Service connects to the DB Service and Logging Service via gRPC over these internal addresses, and the DB/Logging services connect to PostgreSQL and Kafka in the same way. For external access, I only expose the necessary ports (e.g., NGINX at localhost:8080 and Kafka at localhost:9092) to the host.

services:

# database

postgres:

image: postgres:17

container_name: postgres

hostname: postgres

environment:

POSTGRES_USER: dncc

POSTGRES_PASSWORD: dncc

POSTGRES_DB: goodsstore

ports:

- "5432:5432" # Expose PostgreSQL to "local:container"

volumes:

- pg_data:/var/lib/postgresql/data

- ./db-init:/docker-entrypoint-initdb.d

# kafka message queue with zookeeper config management

zookeeper:

same logic as codebase provided

...

kafka:

same logic as codebase provided

...

...

ports:

- "9092:9092" # For internal Docker use

- "9093:9093" # For external access

...

kafka-topic-creator:

image: confluentinc/cp-kafka:7.7.1

depends_on:

- kafka

# This helper should not restart automatically after it finishes

restart: "no"

entrypoint: >

bash -c "

/bin/kafka-topics --create --topic log-channel --bootstrap-server kafka:9092 --partitions 1 --replication-factor 1;

"For our implementation

##### YOUR SERVICES GO BELOW THIS LINE #####

db_service:

build: ./src/db_service

container_name: db_service

depends_on:

- postgres

environment:

POSTGRES_DSN: "dbname=goodsstore user=dncc password=dncc host=postgres port=5432"

# ---------- API 副本 ----------

api1:

build:

context: ./src/api_service/server/python-flask/

container_name: api1

env_file:

- .env

environment:

- LOGGING_ADDR=logging_service:50052

- INSTANCE_NAME=api1

- DB_ADDR=db_service:50051

ports: []

depends_on:

- db_service

- logging_service

api2:

build:

context: ./src/api_service/server/python-flask/

container_name: api2

env_file:

- .env

environment:

- INSTANCE_NAME=api2

- LOGGING_ADDR=logging_service:50052

- DB_ADDR=db_service:50051

ports: []

depends_on:

- db_service

- logging_service

# ---------- NGINX ----------

nginx:

image: nginx:alpine

container_name: nginx_lb

depends_on:

- api1

- api2

ports:

- "8080:80" # external access http://localhost:8080 -> NGINX

volumes:

- ./nginx.conf:/etc/nginx/nginx.conf:ro

networks:

- default

logging_service:

build:

context: ./src/logging_service

dockerfile: Dockerfile

container_name: logging_service

hostname: logging_service

depends_on:

- kafka

environment:

- KAFKA_BOOTSTRAP_SERVERS=kafka:9092

- KAFKA_TOPIC=api-logs

# internal gRPC

ports:

- "50052:50052"

networks:

- default

volumes:

pg_data: # A placeholder volume without any configuration

NGINX:

services:

nginx:

image: nginx:latest

container_name: nginx

ports:

- "8080:80" # host:8080 -> nginx:80

volumes:

- ./nginx.conf:/etc/nginx/nginx.conf:ro

depends_on:

- api1

- api2And inside nginx.conf:

http {

upstream api_backend {

server api1:8080;

server api2:8080;

}

server {

listen 80;

location / {

proxy_pass http://api_backend;

}

}

}NGINX reaches the API instances using api1 and api2 service names, again via the same Docker network.

From outside, I only expose NGINX:

User → http://localhost:8080

NGINX → api1:8080, api2:8080 inside Docker

This configuration allows all microservices to communicate reliably inside the Docker network while keeping internal ports isolated from the outside.

8. Experiments

Swagger UI / Kafka Experiments + Simple QPS Benchmark

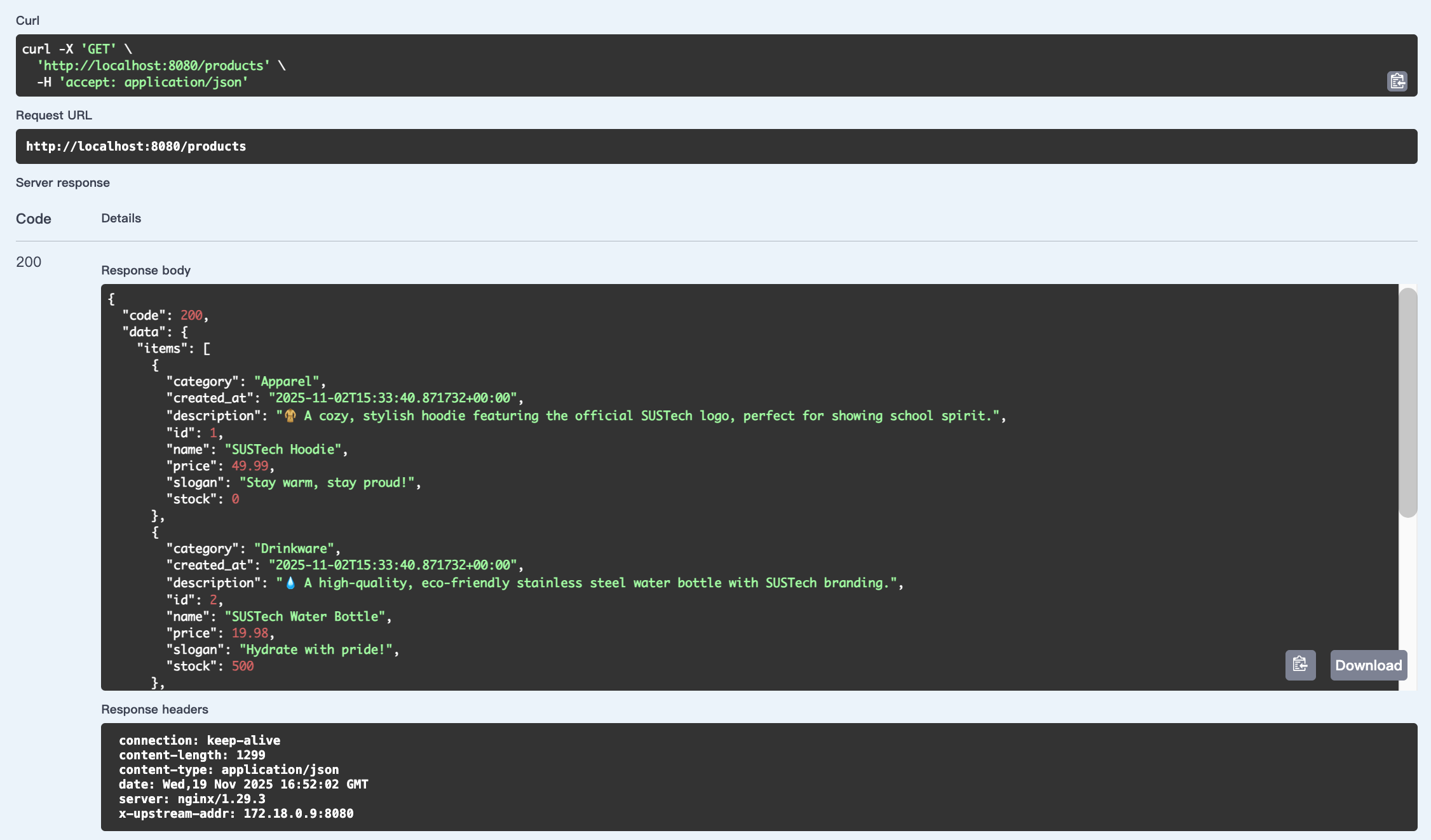

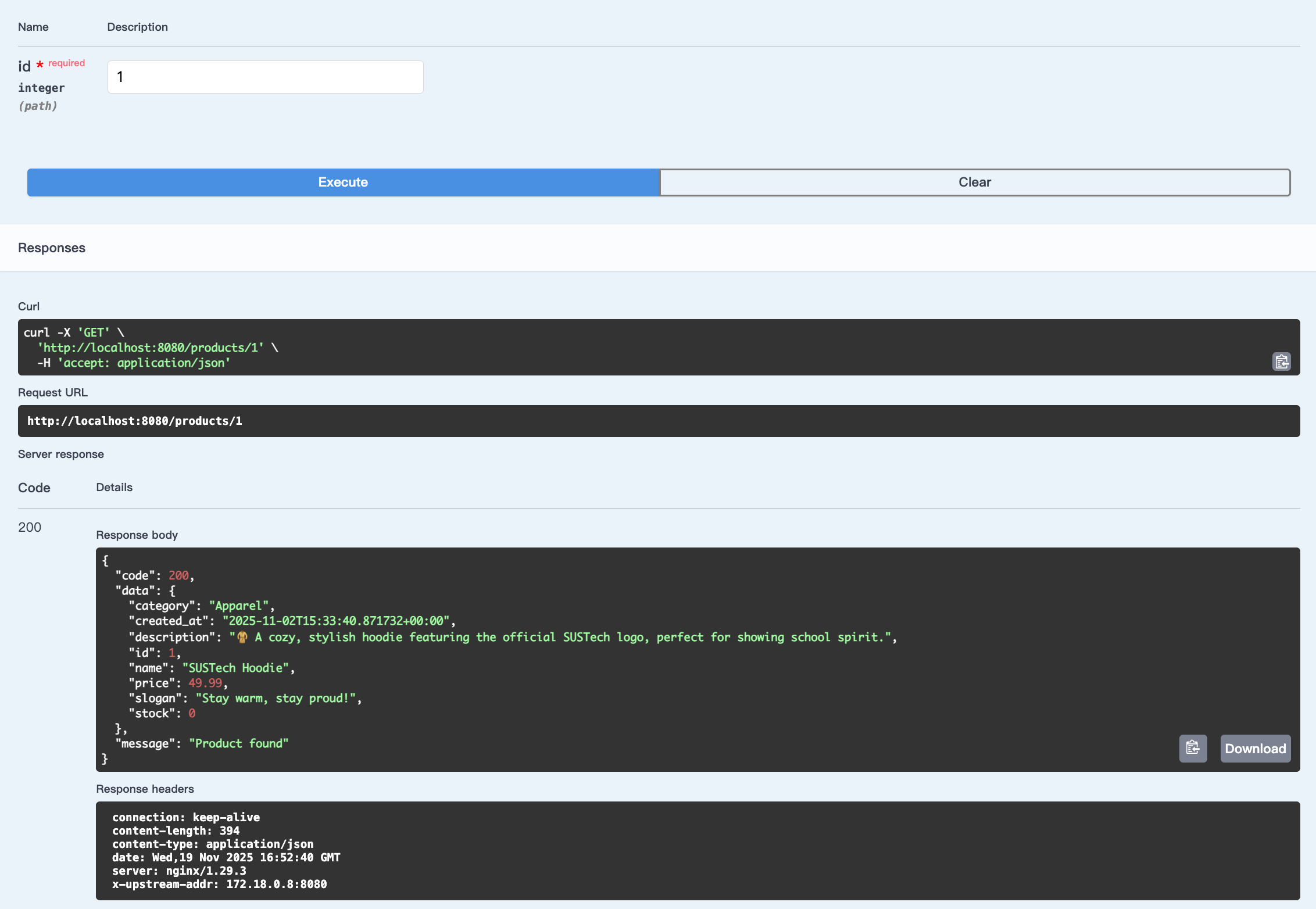

Swagger UI

I mainly use Swagger UI to test my API Service.

First, User can see our website and its products:

"/"

"/products"

"/products/id"

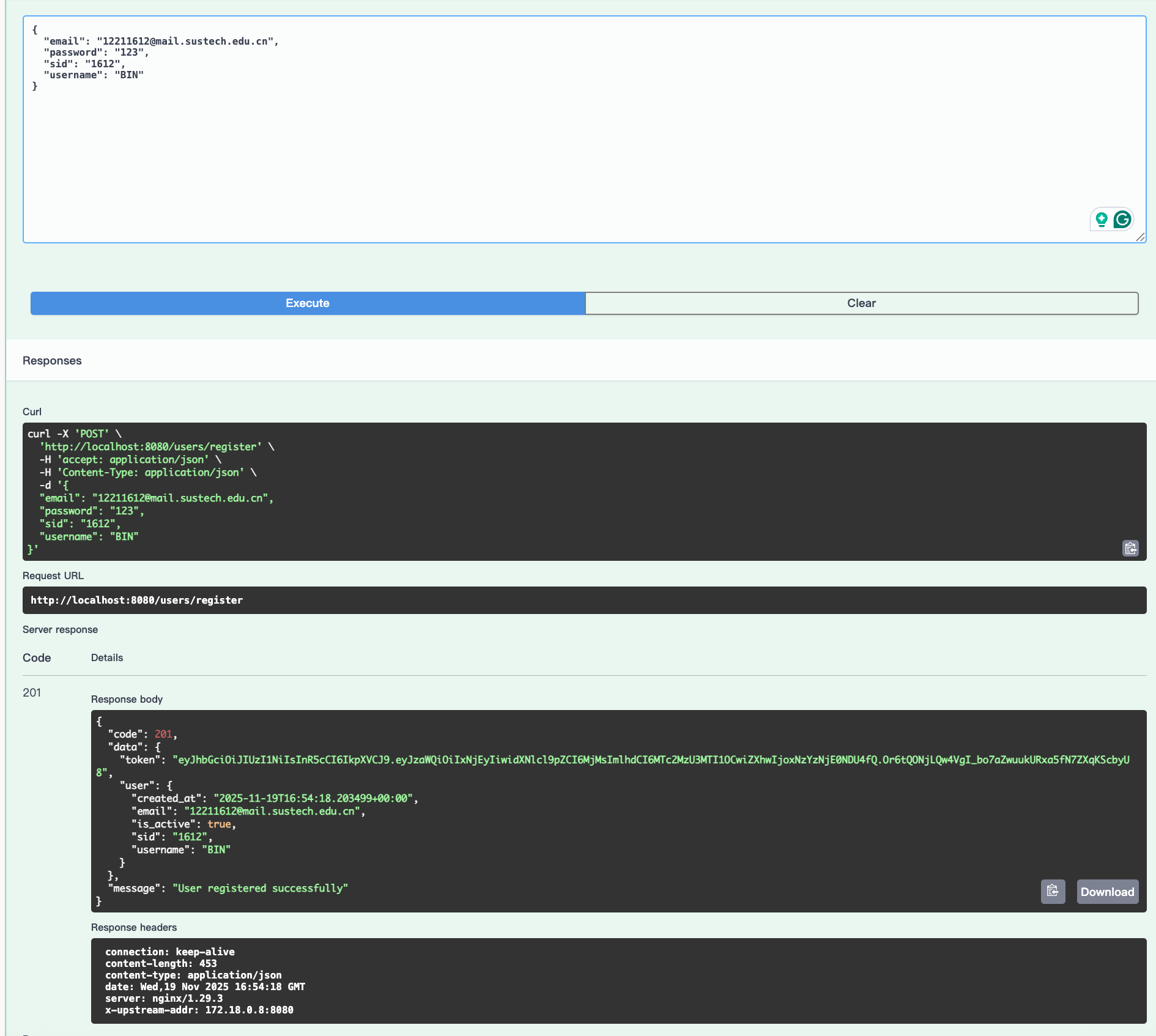

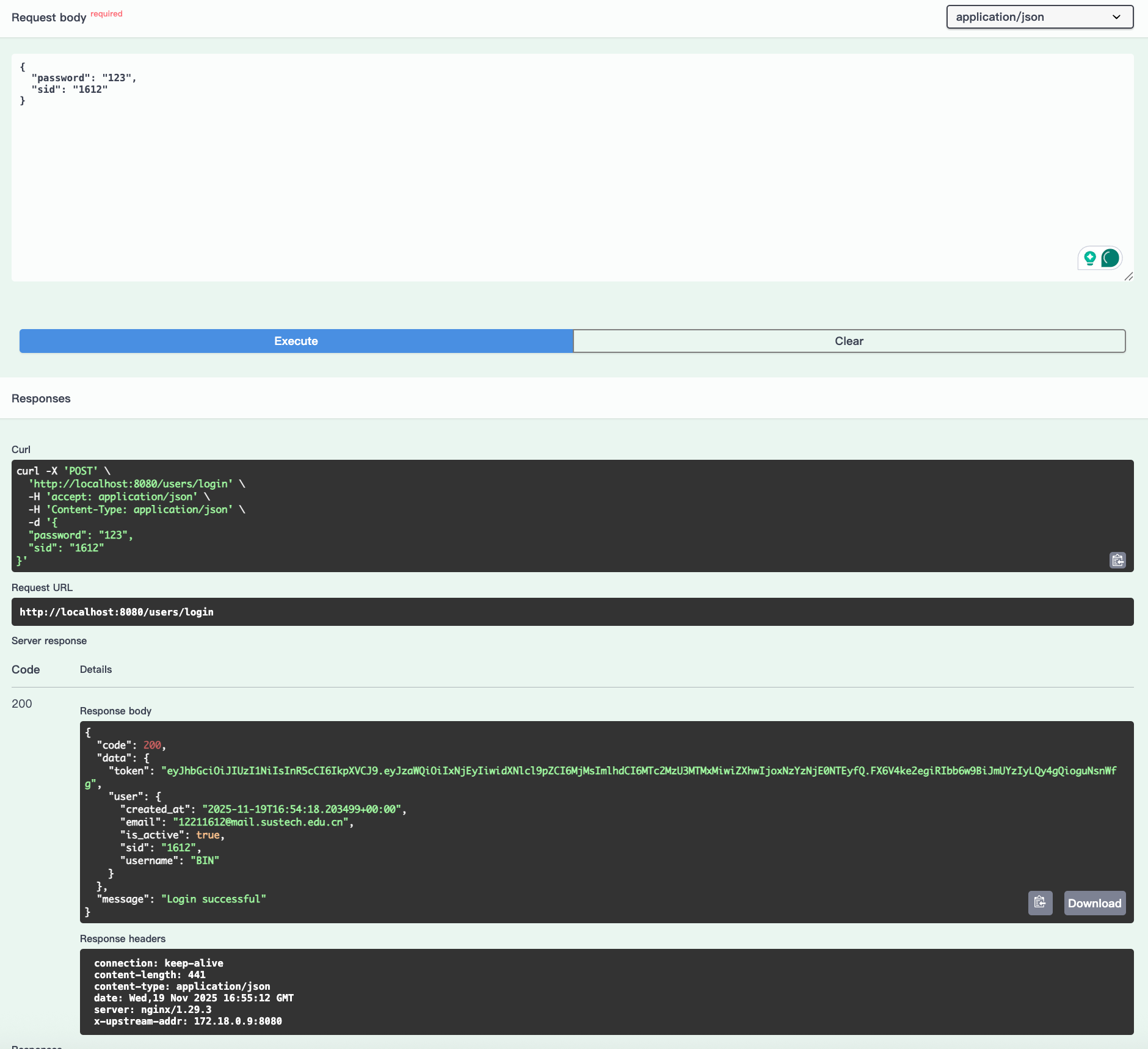

Then, user can register:

User can login and get a JWT. And we won't get passwd back.

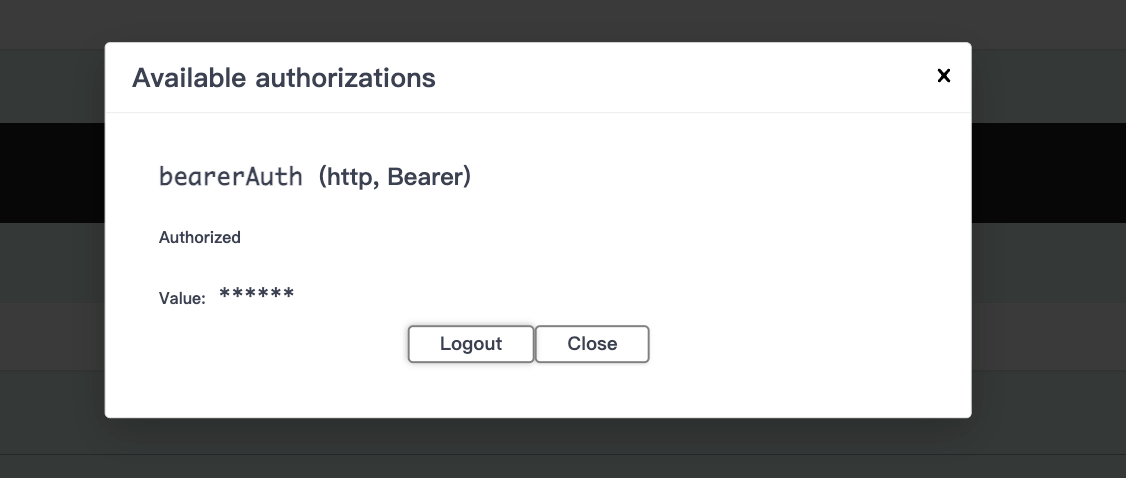

We can put the JWT as we login:

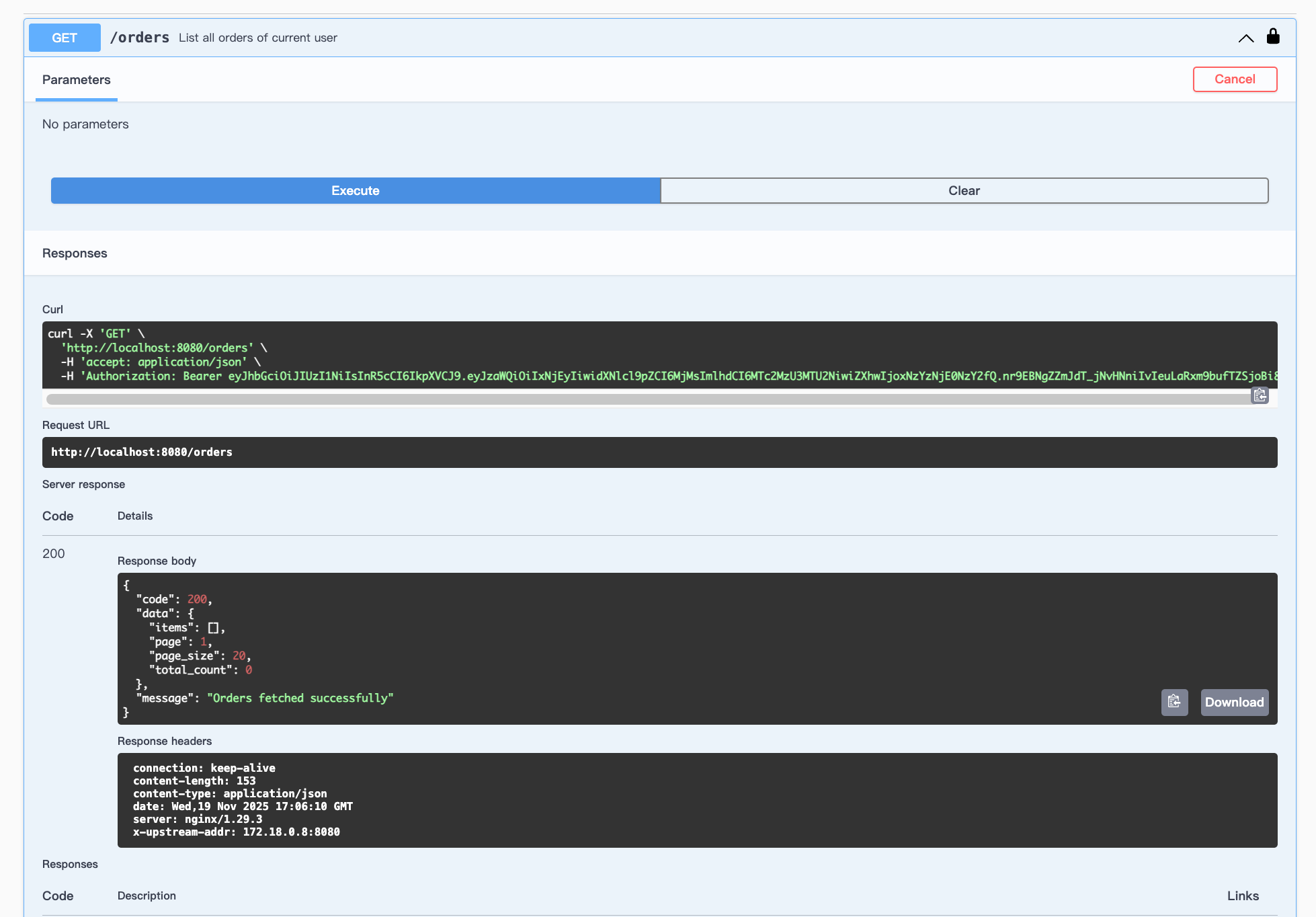

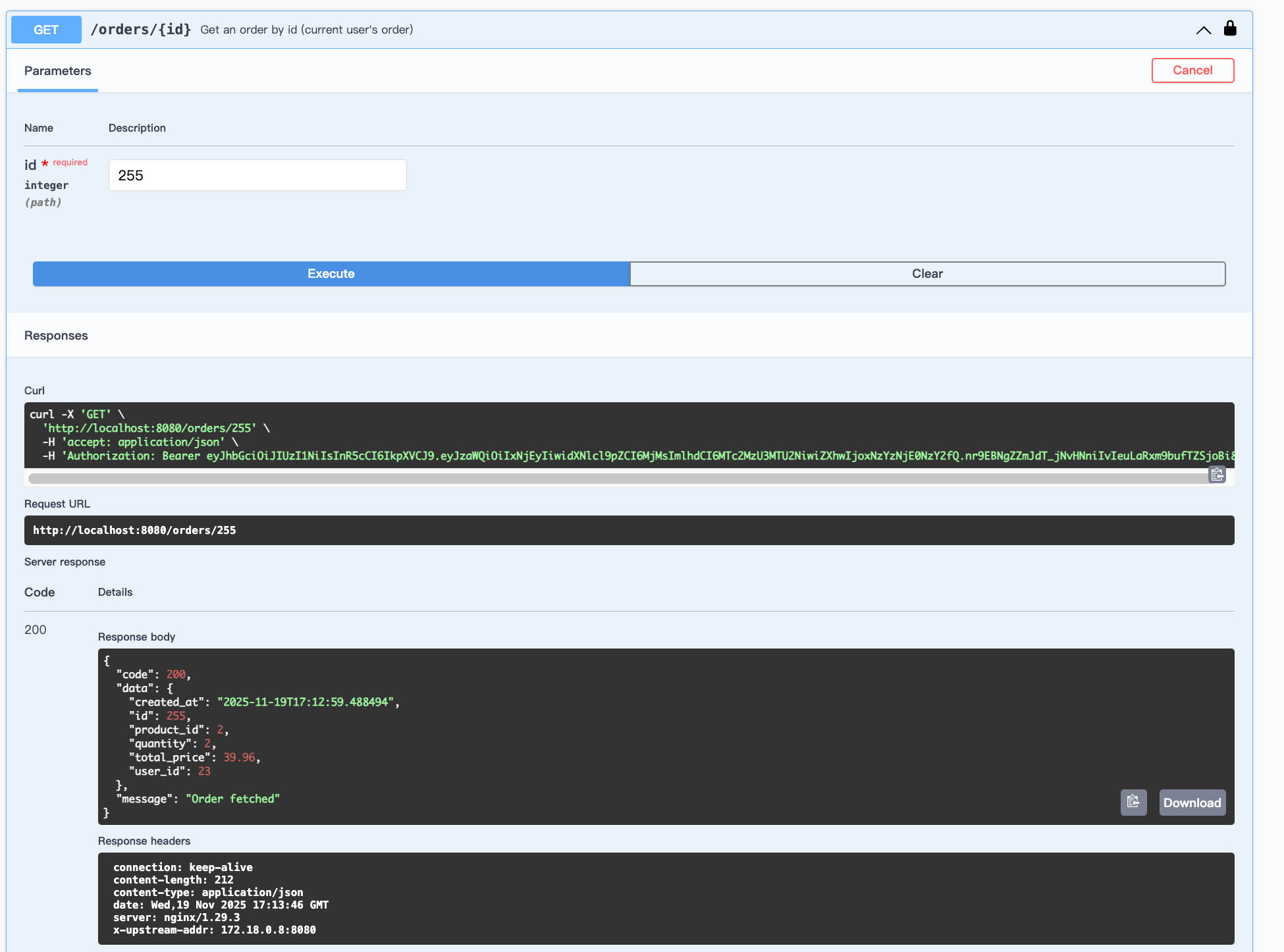

Get orders:

Place Order

{

"product_id": 2,

"quantity": 2

}

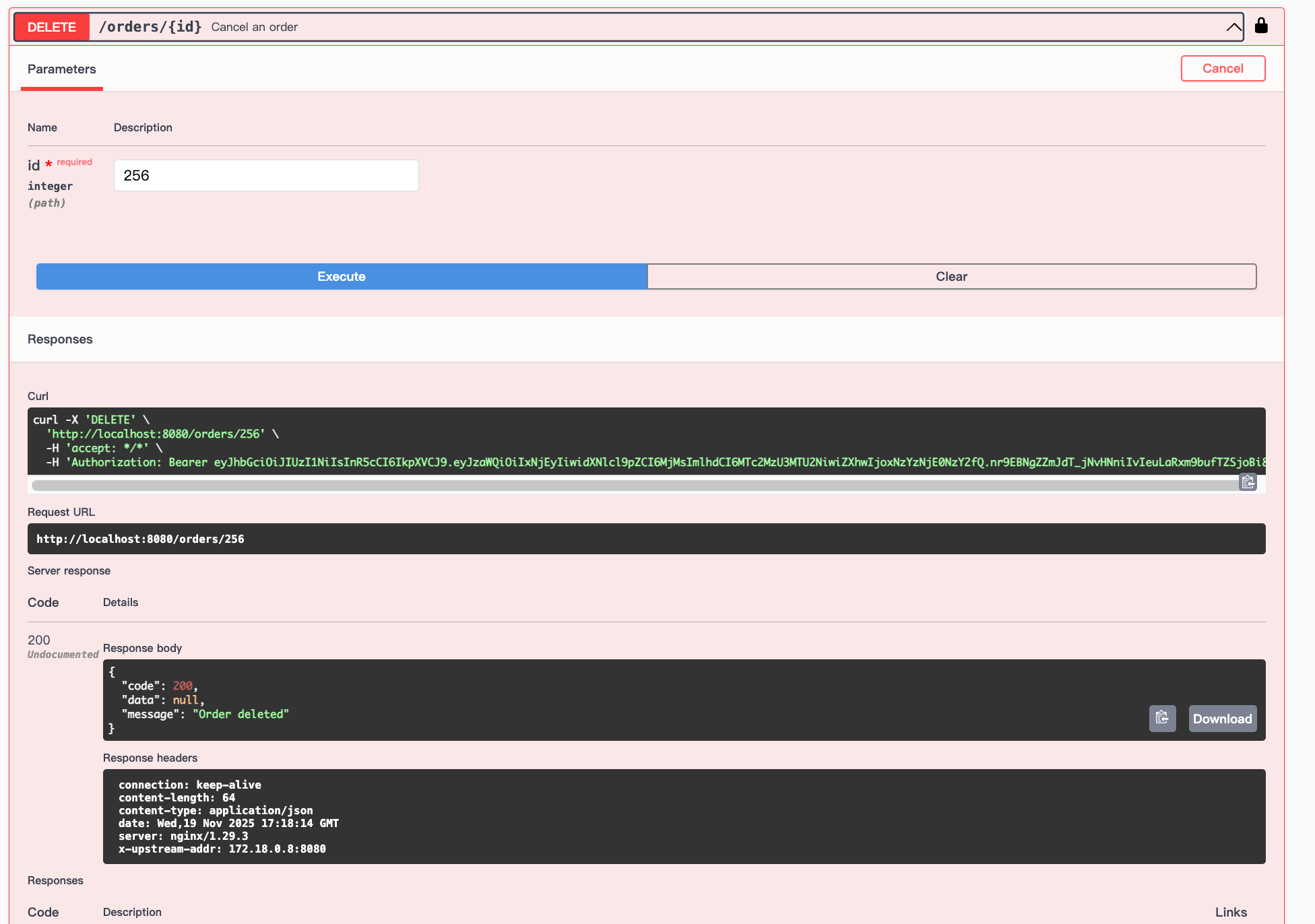

The order id is 256.

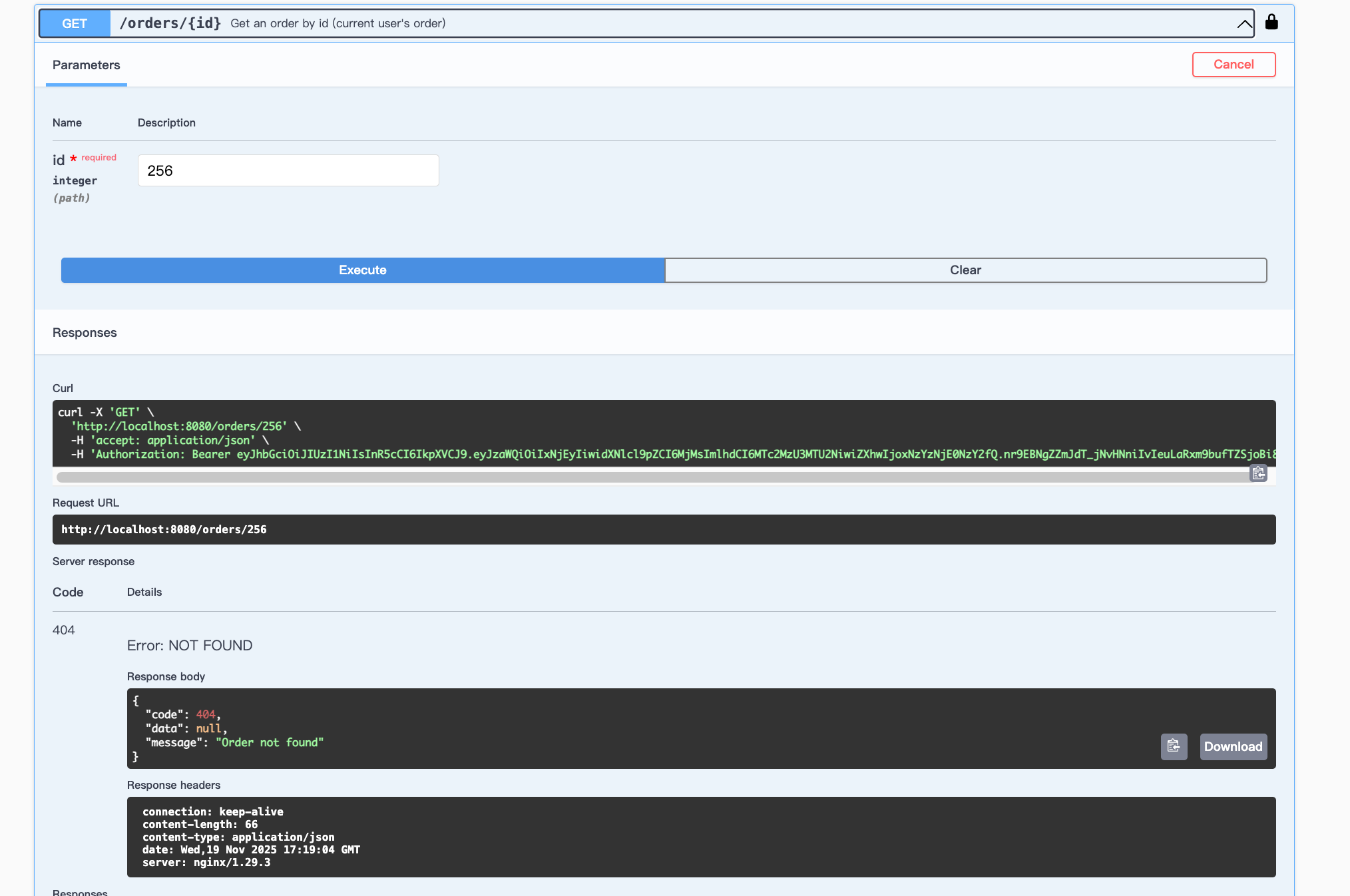

We can delete it:

Then:

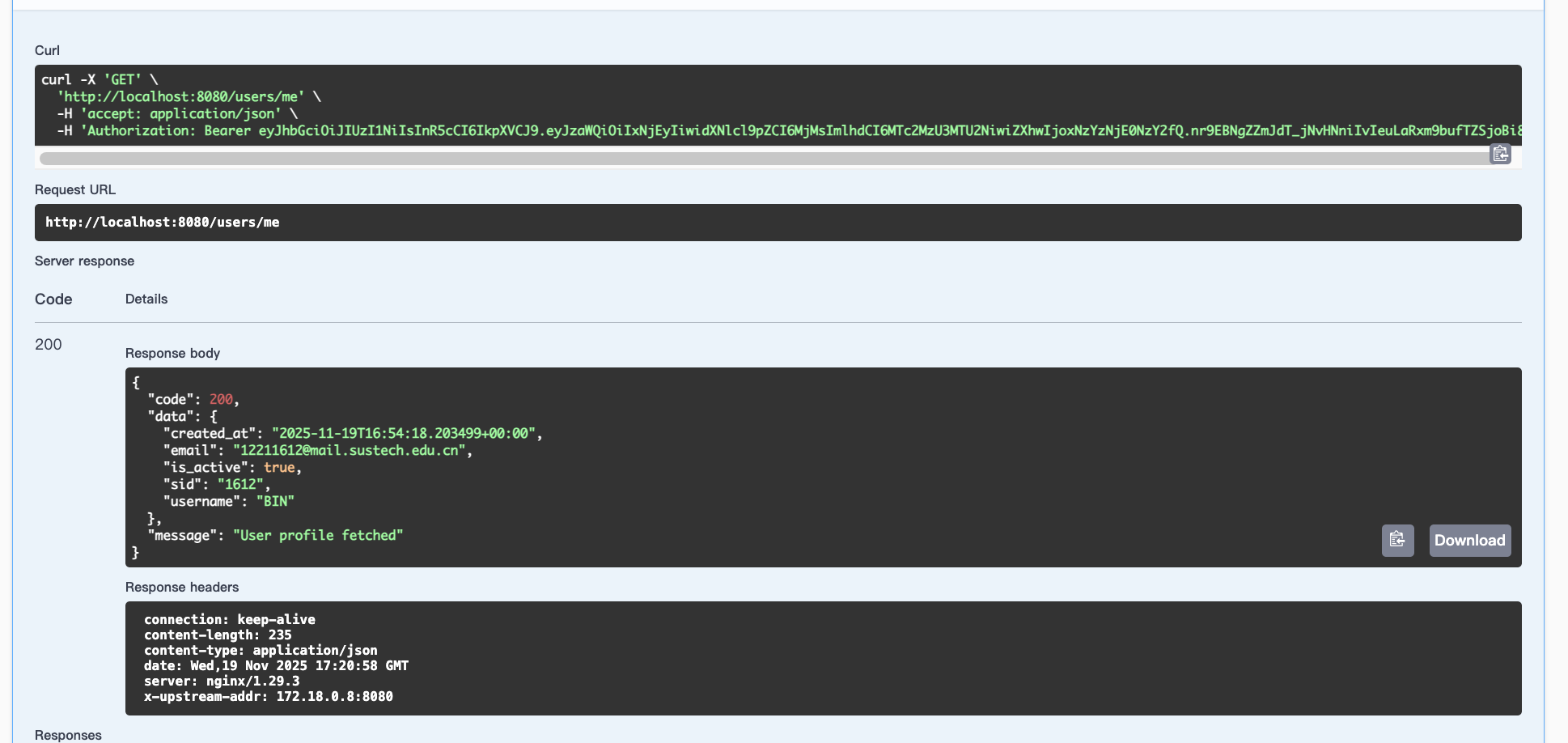

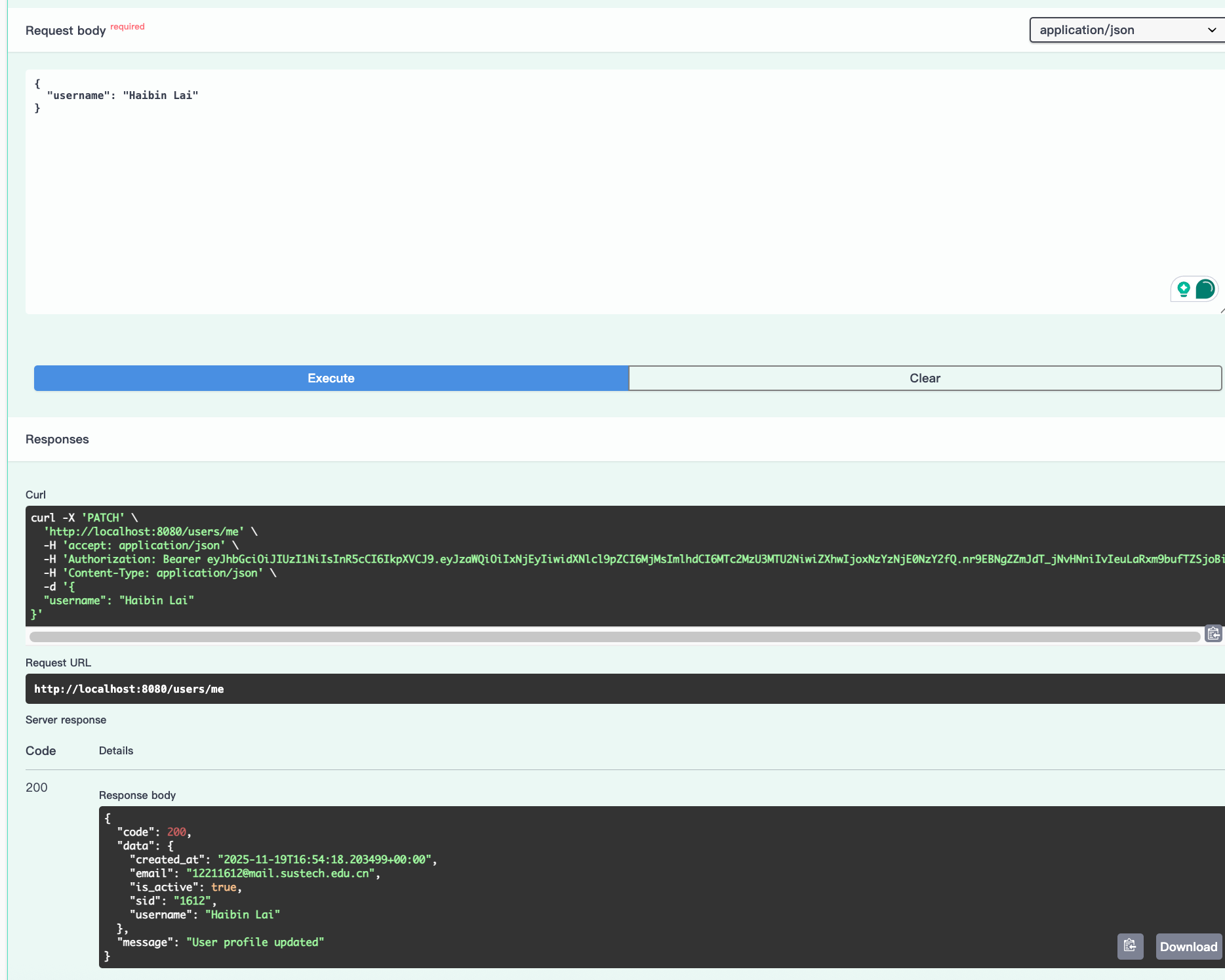

Check my account status:

GET /user/me

Update my account:

PATCH /user/me

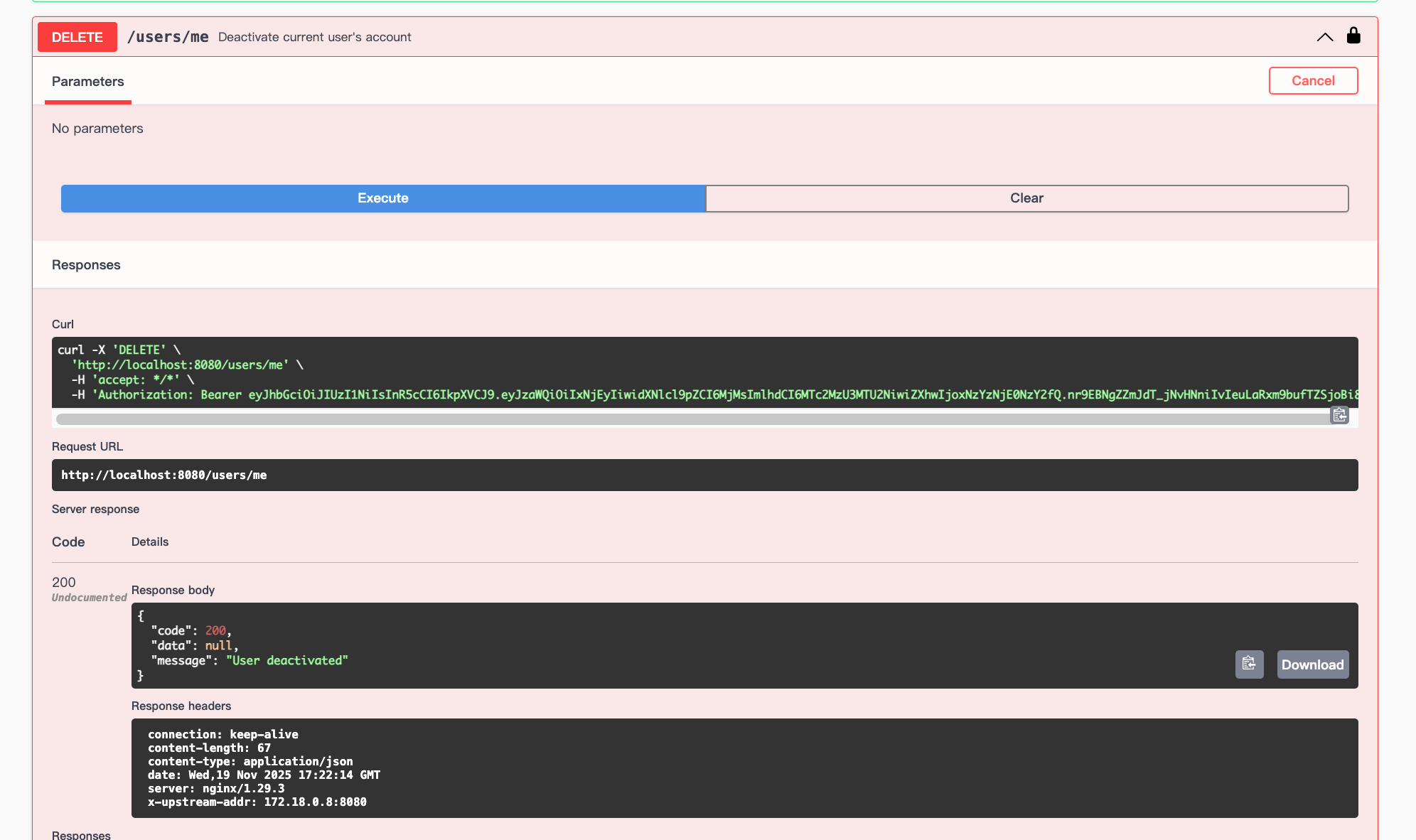

Delete the account:

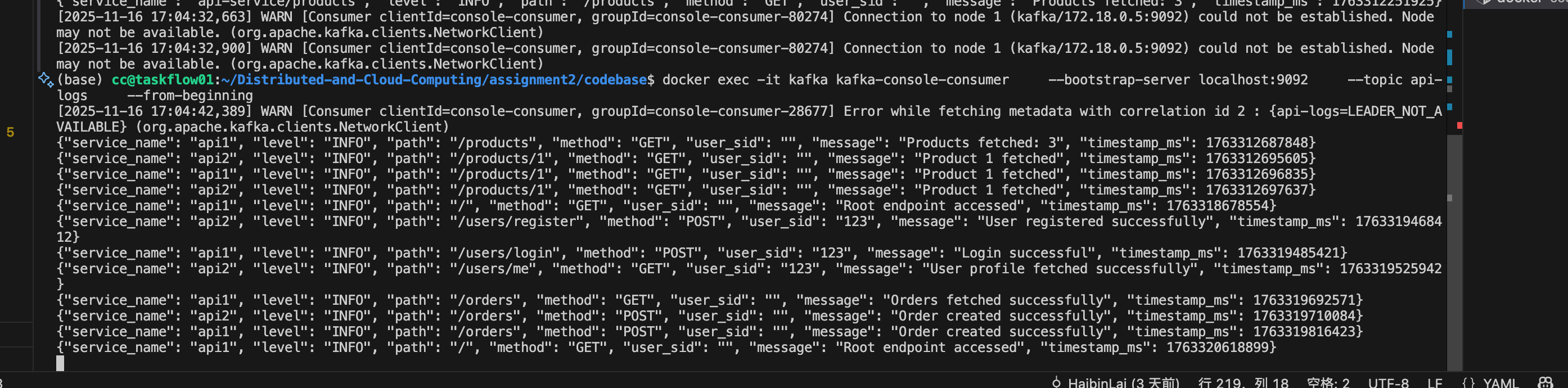

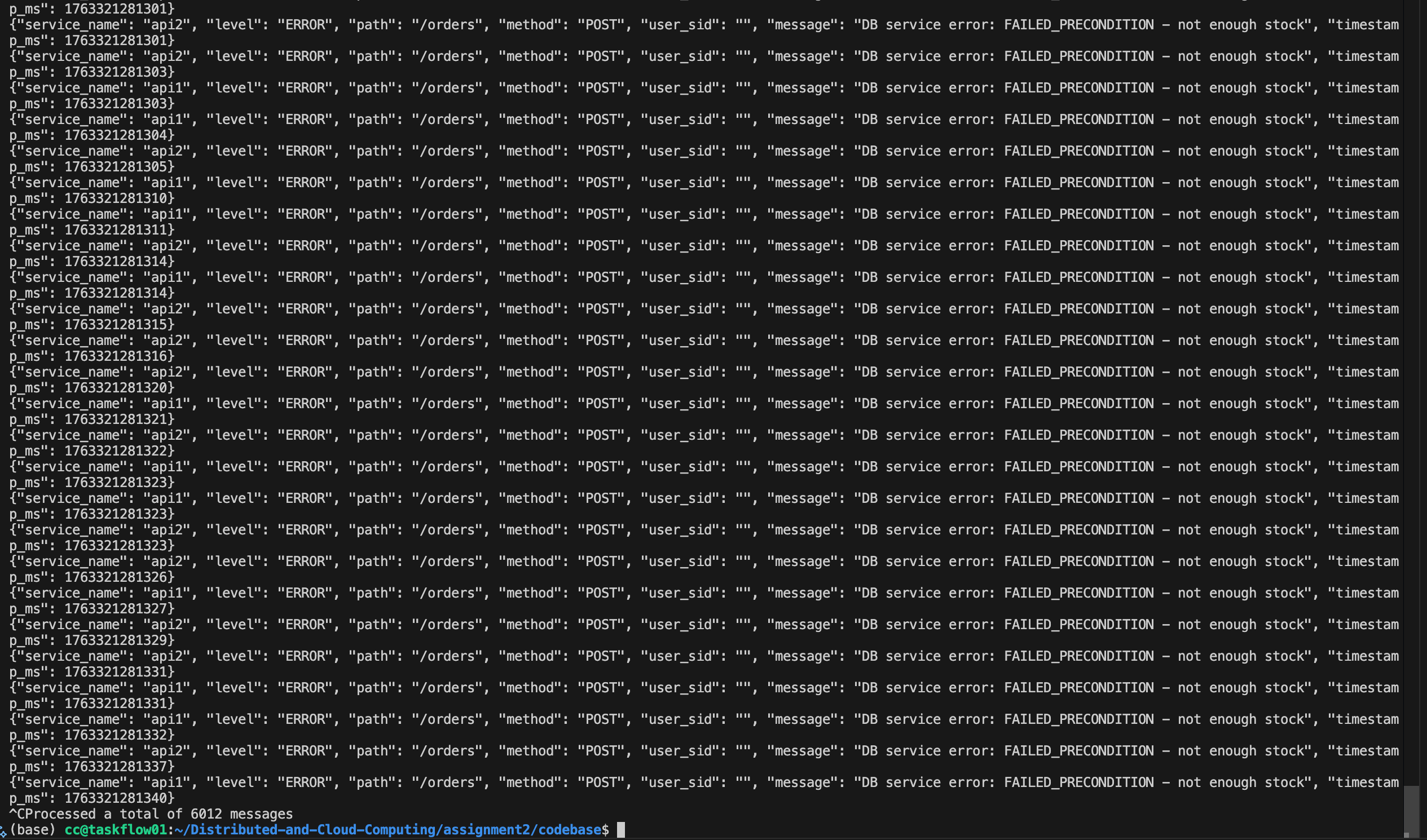

Kafka topic

run

docker exec -it kafka kafka-console-consumer --bootstrap-server localhost:9092 --topic api-logs --from-beginningwe can see the log from admin side.

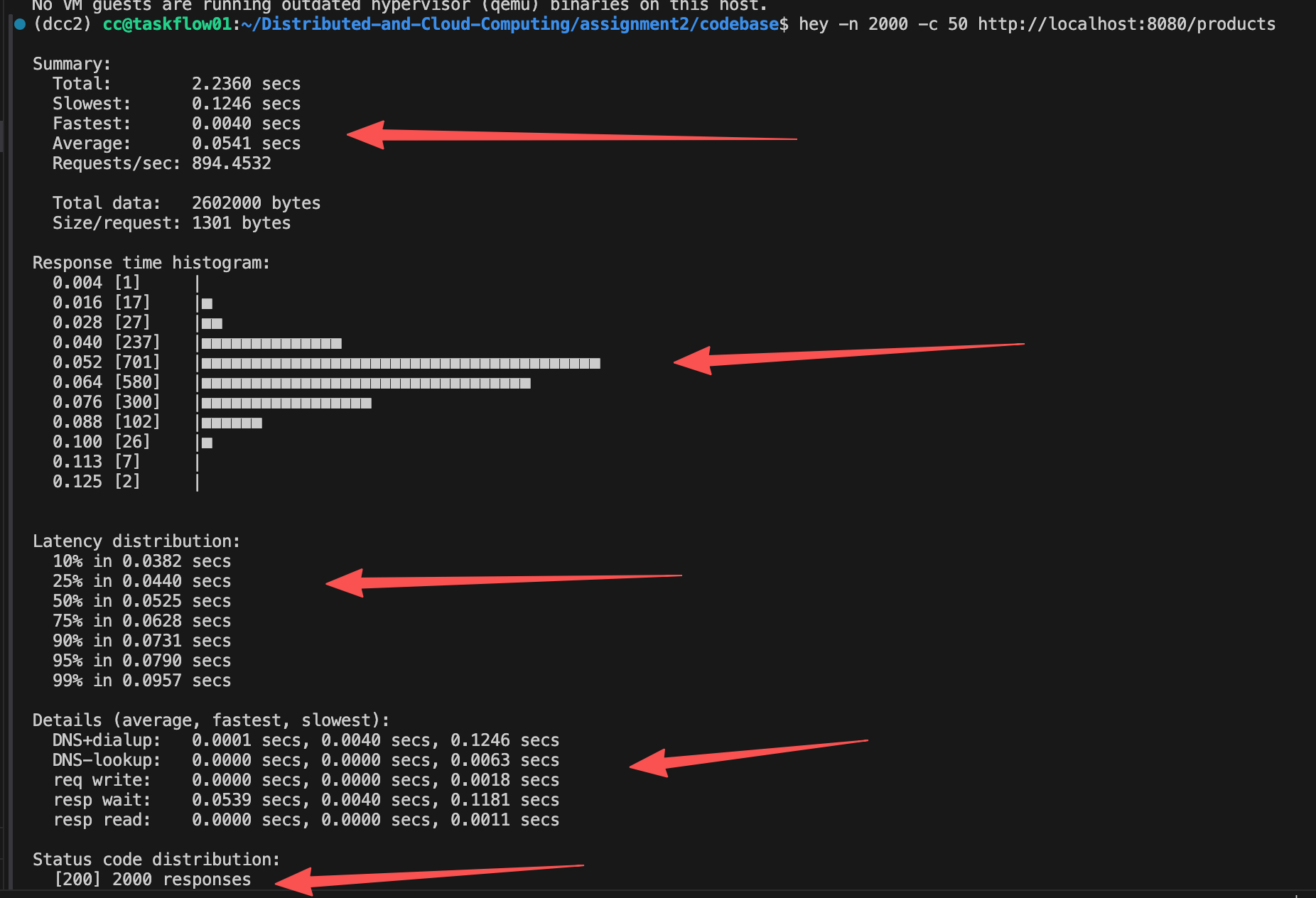

QPS Benchmark

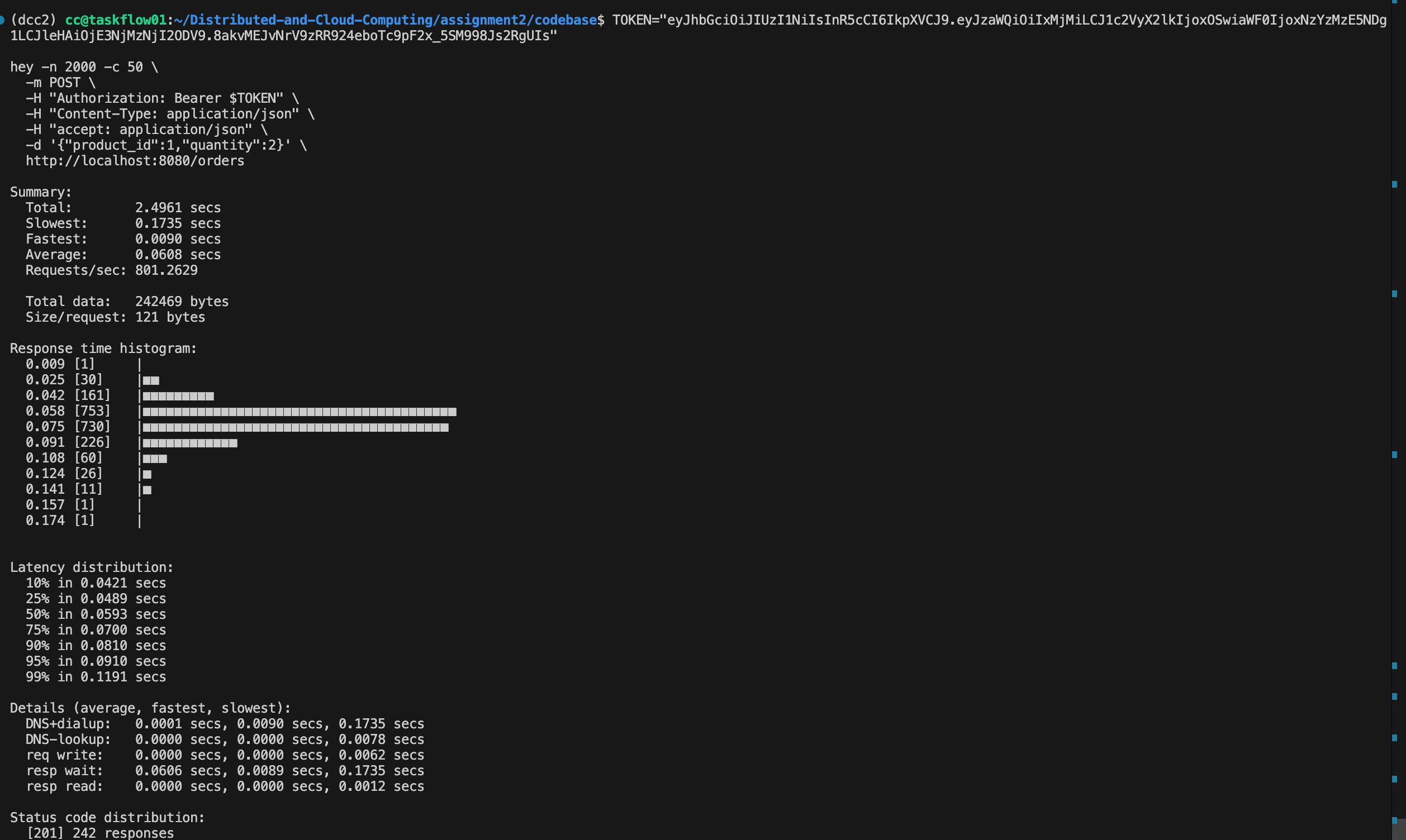

we use hey to benmark our APIs.

sudo apt install hey

# Run the testing

hey -n 2000 -c 50 http://localhost:8080/products2000 means we request 2000 times, while 50 means 50 queries at one time.

There will be several info we can get to see if our API is fast enough, and what's the bottleneck:

As we can see, the QPS of our API is 894. According to the chart, most of the response time lies in 0.088s. And 95% in 0.0790s. The bottleneck is the DNS dialup (from docker) and resp wait (database service query).

So, a good way to improve the latency may be using some of the memory database like redis. Redis can store and return the query result in memory instead of the SSD/HDD.

This shows the reason why so many companies try to use Redis.

We also test the api of /orders , with Auth. As we can see, this time resp wait increase, since we have more complex transaction logic.

(tips: since we only have 484 products (Originally 500, some of them I ordered before), only 242 requests success. But this maybe a good case for double-eleven day “秒杀” or why our school choose class systems fail all the time)

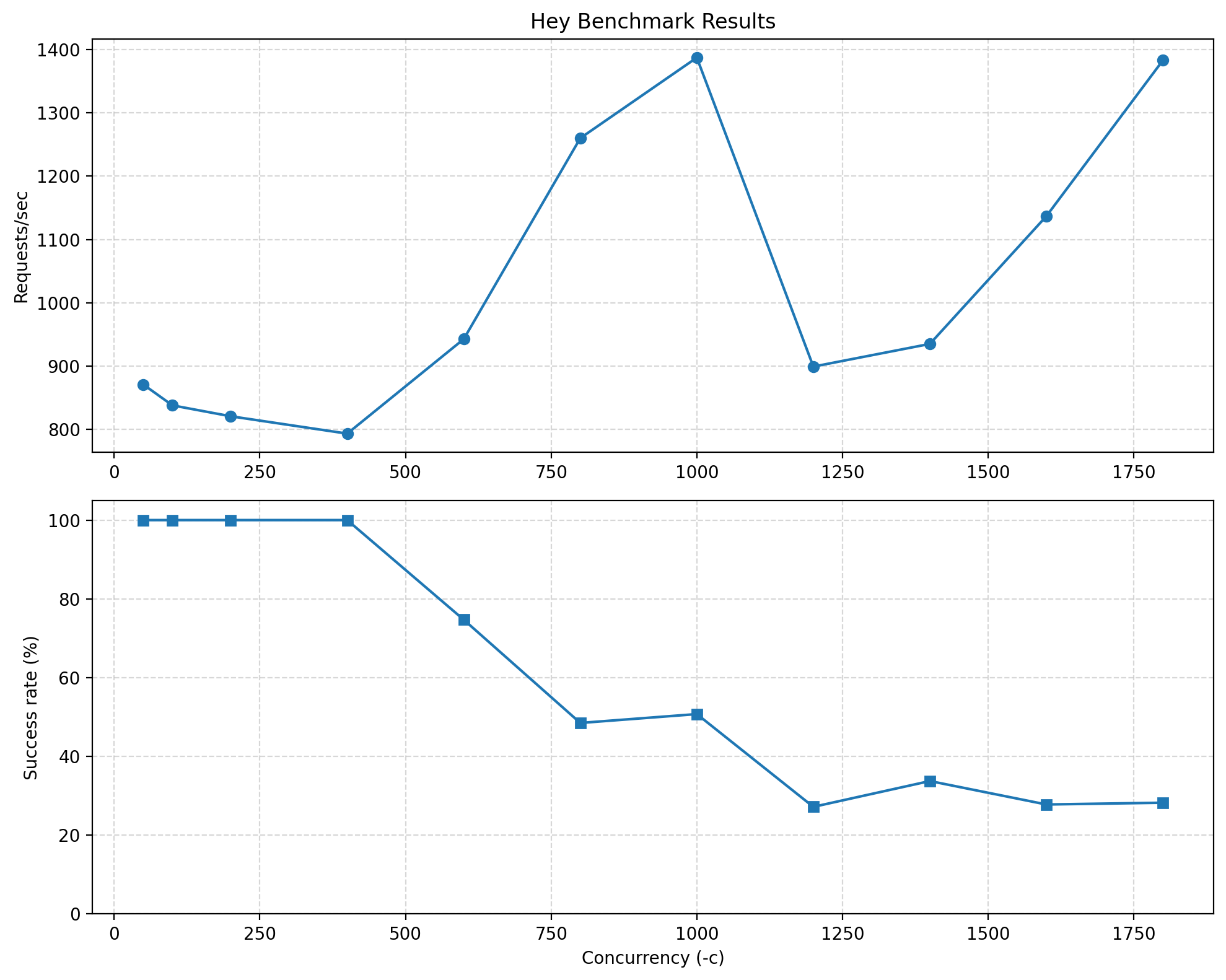

Understanding NGINX

Here I do a very simple experiment on Request. As we increased the concurrency from 50 to 400, the system was able to handle all 2000 requests successfully, and the throughput (Requests/sec) gradually increased.

Beyond a concurrency of around 600, the system started dropping requests: many connections failed at the transport layer and never produced an HTTP status code, eventually falling below 30%, while the apparent Requests/sec curve peaks around 1000 concurrency, drops, and then unexpectedly rises again.

As you can see, when concurrency is 400 (that means 400 users request at one time), the success rate is 100% and dealing speed is about 800. This maybe the maximum number that system can take. After that, system can not deal with some request.

Why the Success rate go down as concurrency increase

When concurrency becomes too high for the system to handle, many requests begin failing before they even reach the application layer. This happens due to limits in the web server (NGINX), OS file descriptors, or the backend worker capacity.

Once these limits are exceeded:

- New TCP connections are rejected, reset, or timeout

- These failed requests never receive an HTTP status code

- Only a subset of requests successfully passes through NGINX and reaches Flask

- Therefore, the number of successful HTTP 200 responses decreases

So the success rate decreases not because the API behaves incorrectly, but because the system is overloaded and cannot accept all incoming connections, causing many requests to fail at the transport layer.

Why the Request speed reach limit at 1000 then drop, then rise up:

This is mainly because of NGINX.

This behavior is a typical artifact caused by connection limits inside NGINX and how hey calculates throughput.

1) NGINX has a connection limit (~1024 worker_connections)

Once concurrency approaches or exceeds this limit:

- Only a fixed number of connections are allowed to be active

- Extra connections fail immediately without entering the queue

2) Failed connections return instantly, reducing total test duration

hey computes Requests/sec as: successful_requests / total_test_time

When concurrency is extremely high:

- Many requests fail instantly (connection refused/reset)

- The total test duration becomes very short

- The small number of successful requests complete quickly

- Therefore,

successful_requests / timemay appear higher again, even though the system is overloaded

3) This creates the illusion that the throughput rises again

In reality:

- The backend is not performing better

- The increase is an artifact caused by:

- NGINX rejecting excess connections immediately

- hey shortening the run duration

- Only the “lucky” in-limit connections being measured

So the rise after 1000 concurrency is not true performance gain, but a side effect of NGINX’s connection limit and hey’s measurement method.

Therefore:

The Requests/sec curve peaks, drops, and rises again mainly because of NGINX’s worker connection limits and how hey measures throughput.

Some we learn innerly: The Power of NGINX

This behavior actually highlights one of the advantages of using NGINX.

When the concurrency exceeds the server’s capacity, NGINX intentionally rejects excessive connections immediately. This “fail-fast” behavior prevents resource exhaustion, protects backend services, and ensures that the valid in-limit connections can still be processed quickly.

In other words, instead of letting the entire system become slow or crash, NGINX performs graceful degradation:

it sacrifices excess traffic to preserve the performance and stability of the remaining requests.

Kafka now is very crazy:

For most of the CRUD scenario, the QPS is above 800, which is ok for a school market backend. But to increase, we can increase the number of thread in DB threadpool, gRPC pool, and API Server.

More over, we should develop a distributed cloud system to support them with more QPS support (This is the purpose why we attend the class :0 ).

There are so many other benchmarks we can make, like NGINX scheduling strategy, thread number, etc. You can try it later.

9. Possible Improvement

There are still many things we didn't do:

- Soft deleting: we didn't delete data from db. Instead we just update a key into 'false'.

- Multi-node: we can publish different docker instance in different nodes. Probably a K8s is needed for better management.

- Some of the strange bugs that may happen.

- Experiments on different thread number in threadpool

- NGINX strategy

- Multi language that may differ the QPS

But I think a good software, is not only equal to a software that without bugs/improvements. Win 7 is a good software, Linux is a good software. The scalability, user friendly, safety enough, easy to develop, these features are also important features.

So although we have so much to do, still we have done so much. And that's a wonderful journey so far!